Weak, as Far as Weeks Go -- Pt II

February Third

We met at the office, early the next morning. Troy had stopped to grab a bunch of coffee and we all but ransacked the office for anything we might need that night-- monitors, whiteboards, a fire-hazard worth of power strips. We split up into two cars and took off to meet up with everyone at the hotel.

Lights

It was a pretty ritzy place. I spent like $20 on a turkey club. We weren't allowed to bring outside food and drink, so we definitely didn't smuggle in Red Bull.

There was still a good amount of dashboard work to do, but I was anxious to get started and so I walked around awhile.

Outside of the conference rooms we'd booked, there were a number of really great abstract art pieces. I sat and zoned out for awhile, admiring them. I thought about how nine months ago, I'd spent most of the summer telling anyone who would listen about this "Modern Art Deep Learning classifier" I wanted to build (but never did). I'm all too familiar with what it feels like to lose steam when a hobby starts to feel like work. But as far as "things I got distracted by instead of working on that side-project" go, I think this presidential campaign takes the cake.

I had a few instances of "wait, where do I know that face?" and the answer was uniformly "oh, The News™." I'm like 80% sure I saw Nate Silver. It had all become very real.

We dove back in and put the finishing touches on the dashboards. But after a quick dry run, we'd found that the screens that we planned to project them onto were a lower resolution than we'd developed them for. No bother, we had a few last-minute metric additions we wanted to make, anyhow. It was tedious work, changing one thing and watching it break something else-- like stamping out the bump in a rug. After a couple hours, we'd reached a point where we both satisfied with what we'd made, but not before Troy had the good grace to let me go down to the garage and catch a forty minute nap in my car. The exhaustion of the last three months had hit me all at once and I was rapidly becoming an insufferable ass, I'm certain of it.

And then it was six o'clock. One by one, all of the campaign staff that were milling about started heading out to the precincts they were running. Troy and I changed into something a bit more "camera ready" and made our way to the Boiler Room.

Camera

The senior staff had been in Iowa for a few weeks now, but at the far end of the hall at 950 Office Park, West Des Moines. I'd had a handful of meetings with them between then and now, but they mostly did their own thing. The Suits were already settled in by the time we showed up. As were a handful of people I'd never seen before-- consultants and other hangers on, mostly. The SlackBot folks, plus a few others, parked in the left corner of the room, ready to field any questions or concerns that came up on the ground.

We set up at the front of the room and there were two, 70" TV screens, ostensibly for the two dashboards we'd built. But the Iowa Democratic Party (IDP) data wasn't due to start coming in for another couple of hours, so instead we took someone's Sling credentials and channel surfed all the media coverage. I queued up the SlackBot Dashboard and frantically started writing some code that would handle bad user inputs we hadn't considered. Robin had a Jupyter Notebook with a direct data feed set up to answer any questions that our dashboards couldn't.

At 7:02, SlackBot data started to pour in.

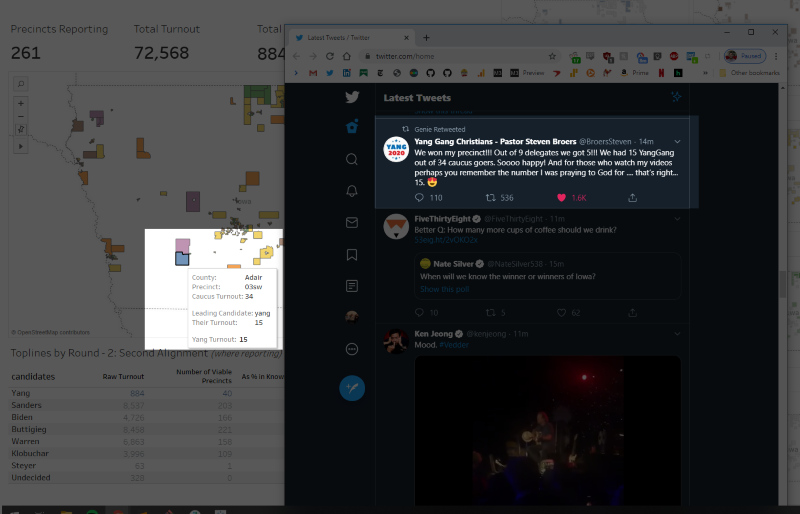

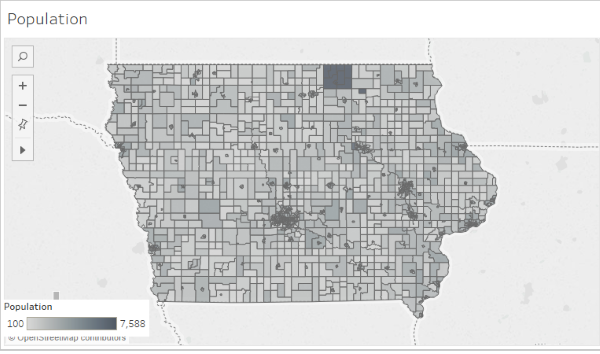

Around the state, First Alignments were resolving and splashes of color began appearing on the sterile, white map of Iowa we'd been staring at. Our SlackBot was working, and so was the data feed we were listening for. Under header reading "Precincts Reporting" (in 48-point font) was a number that slowly incremented with liberal application of the F5 key. And hot damn, so was "Precincts Viable." But as the first number outpaced the second, we kept reiterating that only a fraction of the precincts had people using our app-- it was still too early to get ourselves worked up either way.

And so we spent the next hour and some change, constantly refreshing the dashboard and poring over every little change we saw. I was bowled over by the sensory memory of playing "Spot the Difference" in the Highlights Magazines I'd grown up reading. On the TV to the right, some talking head was walking around a gymnasium, explaining what the caucus was to the viewers at home. A round of applause would break out every time the camera would pan and catch our supporters in the background.

As the pace of incoming data slowed, I switched my laptop's projection settings from Duplicate to Extend, to free up my screen for some nervous Twitter scrolling. It didn't take long at all to see how our night was playing out as Precinct Captains fired off their updates to the world. Moreover, it was a shot of pure adrenaline to open up my feed and see that the data capture was working!

7:45 rolled around and I closed Twitter and opened up the dashboard watching the IDP data feed. They were set to start releasing data around then. Civis, our cloud data provider, would be listening for it, we expected to probably see it around 8, 8:15.

Uh...

Let's back up.

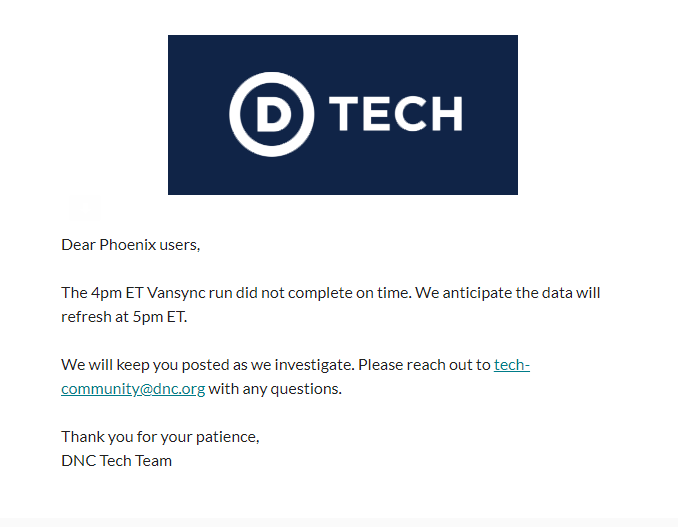

For most of my time on the campaign, the data went from VAN to the DNC to us once a day. Sometime between midnight and 6 AM the data would land on our servers, like clockwork.

I didn't think much of it when their attempts to increase the migration cadence got off to a rocky start.

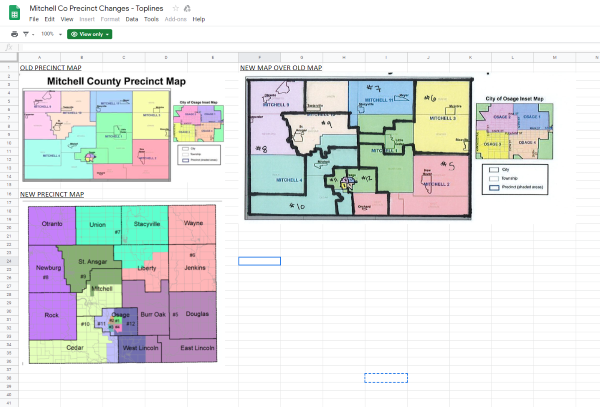

It was annoying but manageable when, for reasons essential to our democracy, they redistricted an entire county three weeks to caucus.

It broke our dashboards, but it gave me a reason to play around in QGIS for an afternoon. Lemons, lemonade.

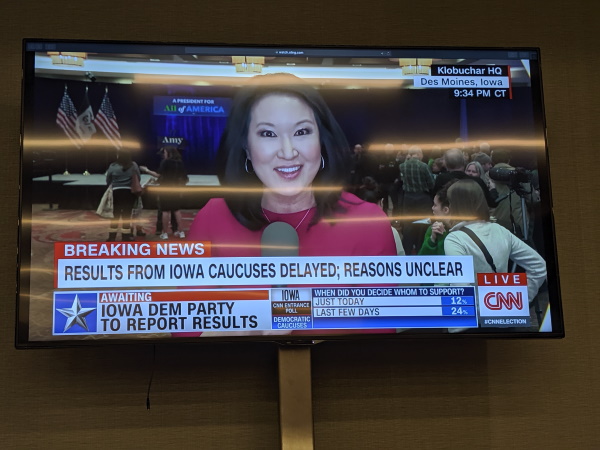

I wasn't quite sure what to make of it when 8:45 rolled around and nobody had any information.

But by this point, most of the room had started checking out. An hour later, the story was quickly morphing into "what the hell is going on?"

By the time the other candidates came out and started declaring victory, the suits were nowhere to be seen. We sat around, refreshing the results on the IDP site to no avail. The folks that had left to be precinct captains found their way back and left again. When we got off a brief call with the IDP and learned the data wouldn't be out until tomorrow, it was the thrown-towel the stragglers had been waiting for. Most everybody packed up and went to the bar.

On the other hand, the State Director stuck around with us until about two or so, helping to shape a narrative from the data we did have.

It's crazy to think that we'd spent the last few days seriously thinking of scrapping the SlackBot, after its failure to launch only days prior. All we could keep saying was "Thank God we didn't." We didn't have the whole picture, but it would have been absolute hell sitting around with nothing.

Andy and Simon, thanks again.

February Fourth

Everyone slept in. I didn't even set an alarm.

The office was a madhouse when I rolled in around noon. Twenty, maybe thirty, people running around, making short work of deconstructing the place we'd spent the last several months together.

Salvaging

As if on queue, everyone that stuck around the night prior arrived within twenty minutes of one another. We got right back to it. Using the SlackBot, we'd collected our own First and Second Alignment data from a few hundred of the nearly 1700 precincts. We tuned back into the potpourri of news stations and settled back into the steady cadence of refresh, refresh, refresh on the IDP data portal. When the first wave of incomplete data got released it was as if a starting pistol had gone off. We immediately set out making the Venn diagram of "what precincts do we have?" versus "what precincts have been reported?"

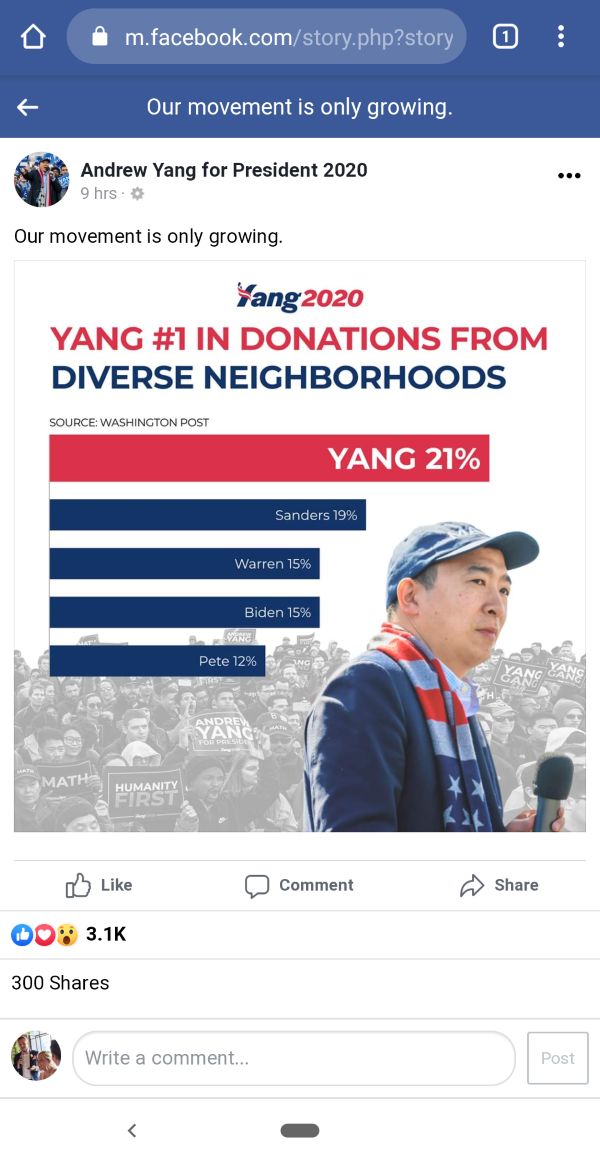

That first push accounted for something like half of the precincts reporting in, and I'll absolutely concede that the union of our data plus their data told a convincing story that we didn't have the night that we thought we were going to. Our first looks supported the Pete narrative that was pushed the night before, but with a huge margin of error. The media eagerly ran with it anyways. Moreover, we noticed right away that nearly all of the precincts that we'd won outright weren't yet included. But every minute that went by was hugely-damaging to what little narrative we could salvage. With several hundreds of precincts still unreported, they just kept running story after story about Pete's convincing win over Sanders-- a race that would end in a 563-562 loss. What an irresponsible trainwreck, releasing the data in waves.

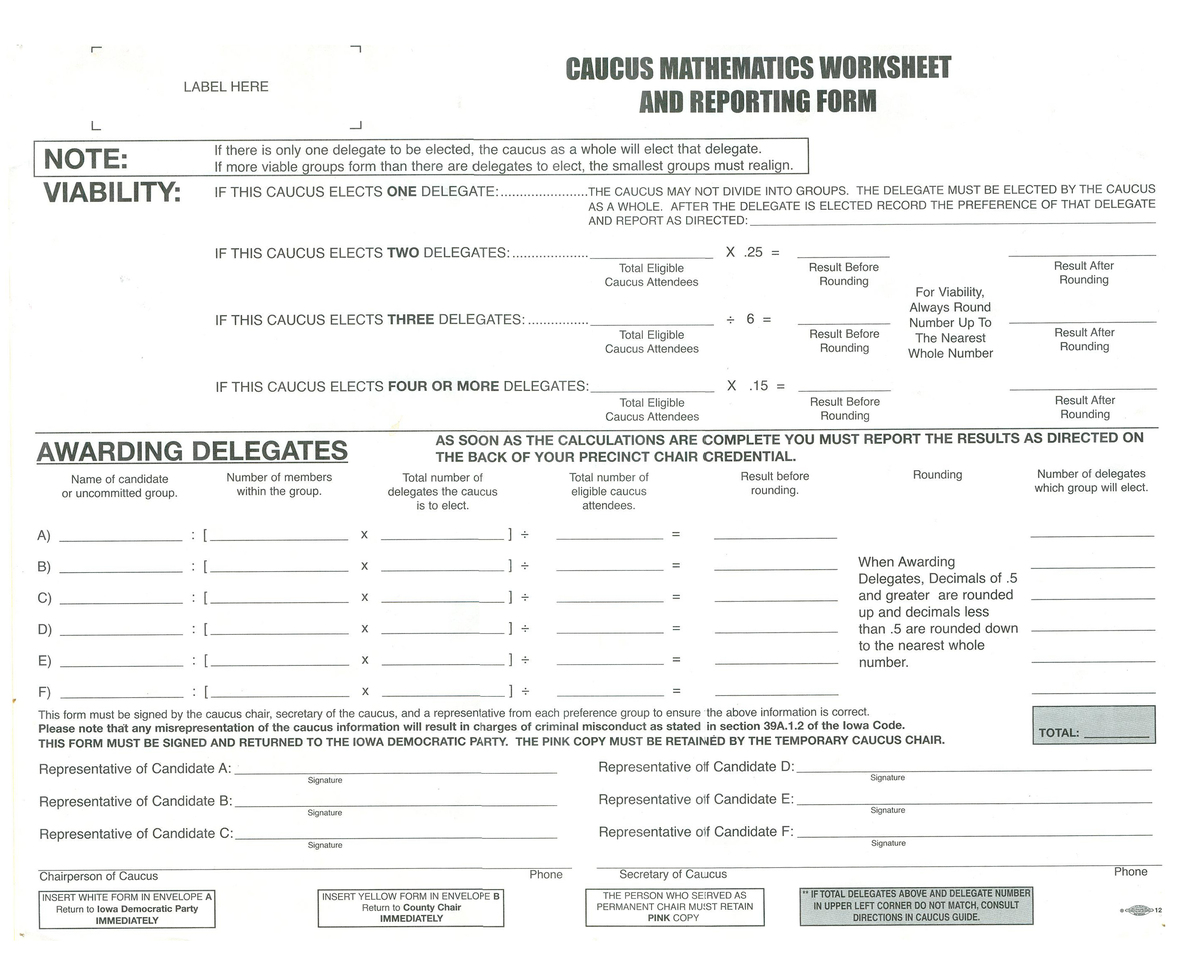

And then we started digging into the intersection of our data and theirs. In more cases than not, looking at the precincts found in both datasets showed a wide range of discrepancies. Of course, these were two platforms generated data by woefully-failable means. It was entirely possible that our folks had over or under reported caucus results into the app. To that same token, the IDP was deciphering the chicken scratch on a couple thousand of these byzantine-ass worksheets.

By that point, the data team had split into two lanes. One team QA'ed our data and highlighted non-trivial inconsistencies. The other loaded the IDP data into various dashboards and notebooks and went back to work mining narrative victories. Our campaign lost more voters between First and Second alignment than any other and we wanted to understand our cross-over support. Even better, we were interested in which candidates we out-performed in the First Alignment, before voters got steered to viable alternatives. As you might expect, the counts of per-precinct "Yang Beat Other Candidate" were about proportional to the overall results, but we were finding interesting patterns in where that was happening. Enough that we felt it was worth sharing with a senior staff that had already bailed from Iowa.

We got a ton done that afternoon and early evening, but wound up having to put a pin in it. It would have been irresponsible to make any sort of statement while the data was only half-released and there was another push slated within the next 24 hours. All of the adhoc reports we'd built would update when it was available and we'd go from there.

More to the point, we didn't want to lose sight of the fact that we were running a marathon together. In truth, the data team had spent the last few weeks "all hands on deck" in Iowa, and regardless of how the caucus data shook out, the next few weeks had New Hampshire, South Carolina, and Nevada all coming down the pike. Then, looking forward to Super Tuesday, we had our work cut out for us, transitioning our codebase to support another dozen-plus states. If you'd asked me then, my (incredibly) rough plan was to head back to Michigan and spend a week or so working remote and then "my whole life is either in storage or in my car, so I'll go wherever you need me to."

In the meantime... when was the last time I ate something?

Recovering

That night we went and enjoyed one of like five nice, sit-down meals I had in Iowa. The data crew was shipping out in the morning and a handful of my original Iowa friends joined in as well. Everyone had spent the last week either been at a different office or on the road with Andrew and so it was an absolute gift to see them again. No task to race back to the office for. No politics at the dinner table. It was one of those places where you pay $60 to have a couple cocktails and try a bunch of interesting dishes and then turn around and go to Chipotle because you were still hungry (we did).

And what a fascinating experience, hanging out with everyone in the suspense between Iowa and whatever was next. I'd seen most of this table every single day for the past month. We came together as mostly-strangers and wound up relying on one another to weather one ludicrous storm after another. As artificial and unnatural as campaigns are to begin with, the bizarreness of everything was perfectly underscored when we found ourselves deep in a conversation that had began: "So... What are y'all like?"

All at once, we were reminded that this was a table of people. Until there was more data to comb through or marching orders to the next thing, it didn't matter what had brought this table together. We went around sharing dumb trivia questions, talked about movies we were eager to catch up on, phones stayed in our pockets as we blindly guessed at what things on the menu meant. As we went around the table sharing hidden talents, I learned that I'd been working with a published architect, former collegiate athletes, dancers, farmers. Then, completely deadpan and with perfect comedic timing, that Robin eats about three family-sized Sabra hummus containers a week. That guy might just be the funniest person I've ever met.

It was profoundly cathartic. Healing, even. There was nowhere I'd rather have been.

February Fifth

After we all said our goodbyes, I went back to my AirBnB and had another solid night's sleep. No huge data pushes had happened overnight so I took my time getting into the office. I spent the next hour or so cleaning up the room the data team had been working out of, intent on leaving things about as nice as we found them. A few trips to my car and I was all packed up. Said my goodbyes to the folks lingering in the office and left to grab lunch with a friend from Field.

It was another nice conversation with a friend, not a work colleague. We'd ordered some fajitas and a respectable count of street tacos when a stranger came and pulled up a chair. He turned to my friend and said something to the tune of "Hey, I saw your MATH hat. Are you guys with the campaign?" And so we spent the next twenty or so minutes with this Sanders organizer who turned out to be pretty cool. Heard the usual spiel of "I really like Yang, but Bernie is my number one." We reciprocated: yeah, Bernie 2016. Yada yada yada. I was too preoccupied with my tacos to get a word in edgewise, but I'd also never had an opportunity to see my friend in full-on Field Organizer mode. By the end of the conversation they'd added eachother on Facebook and my friend had teed him up basically a Yang 101 worth of YouTube, lol

Somewhere along the way, it came up that I worked data on the campaign. Turns out Bernie's folks had also done their own data collection and likewise, were seeing their own discrepancies against what was being released. We circled the drain for awhile about the optics of publicly saying anything about it. We were still waiting for some thirty percent of the precincts to report in, but we had no illusions that clean data would mean the difference between Yang winning and losing Iowa. Bernie, on the other hand, looked to have a much stronger case for pressing this issue. We settled up our checks and I went home to dig back in some more.

I spent the next couple of hours bouncing around my room, cleaning, packing, and hitting refresh on my reports. When more data came out, I'd basically automated everything I would need to share what it taught us. But I couldn't let myself relax. I sat down and started doing my own rooting in the "our data versus their data" problem.

To be honest, I was spending as much effort doing the analysis as I was actively trying to reconcile whether or not I was being a sore loser. The stack of mis-print flyers I was using as scratch paper became littered with questions, partial answers, and a steady increase of profanity. An hour later, I had pages and pages of shorthand notes, crudely partitioned by a bright blue pen into an analytics plan. Save, of course, for that last page where I couldn't give myself a good answer to "what difference is this going to make?"

I started sinking. Yeah, maybe I am a sore loser...

...but then I'd find a record where the IDP said we had zero turnout at First Alignment. In a precinct where we'd reported enough to be viable. What then? Maybe we weren't viable. Maybe our volunteer deliberately put in bad data. But fuck-- we had at least one person there, using our app. Shouldn't we be credited one person? And if I was seeing casual, flippant erasure here, where else was it happening?

I couldn't let myself accept the loss. Not while empirically the "truth" that was being reported was incompatible with our "truth." I couldn't let it go.

And this had nothing to do with curiosity-- with a desire to be right or even to validate how I'd spent my last three months. I'd ran out of ways to respond to the avalanche of "what is going on??" texts and so I didn't. I was scared, too. The quiet, lonely moments between code runs brought an assault of uninvited thoughts: "What was the last thing I said to my friends?" "How am I this surprised? I should have been more equipped than literally anybody to see this coming." "What am I going to say to everyone back hom--" No, fuck that. I have to keep digging. This is bigger than me, and I believe in this so much. I can fix this.

And then my phone vibrated.

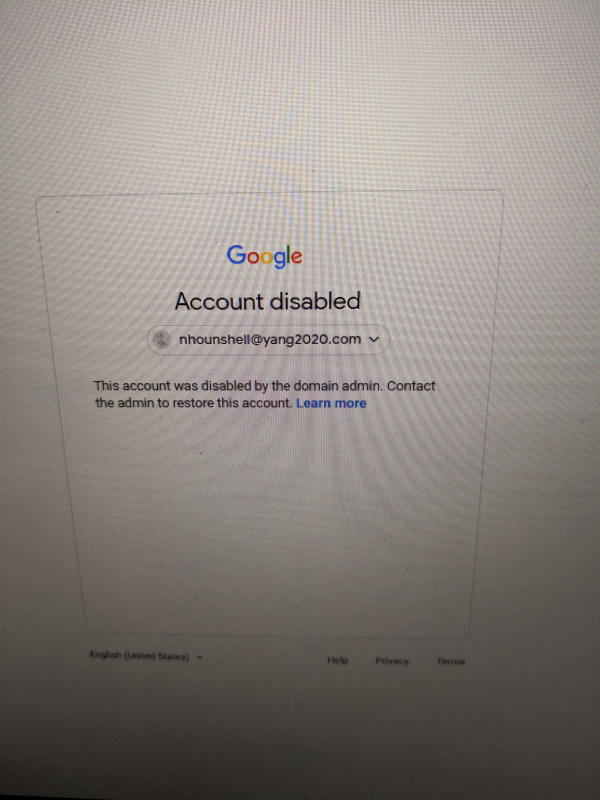

Account action required

nhounshell@yang2020.com

I picked my laptop back up and tabbed over to gmail

And I just... sat, stunned silence coming over me in waves. My lungs emptied in sharp, noiseless breaths and it was all I could do to fight the phantom weight in my chest to fill them again. I pushed the laptop aside and spilled onto the floor, an instinctual answer to the growing spin in my head. Then for good measure, I plead for the empty room to convince me this wasn't happening.

An eternity later, I reclaimed my phone and tried my luck asking the same of everyone I could think to ask. And that's when I learned that Robin was gone. Andy and Kristen were gone. Troy was gone. Data was gone. The Political team was gone. Policy was gone. Comms was gone. Almost all of Iowa was gone. They cleaned house.

Three weeks ago, I'd spent a whole meeting laying out the engine we were building to make decisions in Iowa. The senior staff took to calling me Oscar (I don't get it, either) so as not to confuse me with the other Nick in the room.

Now, five hours after unceremoniously punting me from my login, one of them sends me a form email, sent at 12:14 AM, telling me that the decision was final, that my health insurance was on its way out, and that I could expect severance pay rolled into my final paycheck-- as if I wouldn't have worked for free if they'd asked me to.

And that was it. I never got a call. Humanity First.

February Sixth

I held onto the "maybe it was a bad dream" notion for all of thirty seconds the next morning. Then I rolled over and checked my phone.

I knew this was categorically a bad idea so I deleted the message. Hurt or no hurt, it's not like I'd forgotten overnight why I came to Iowa in the first place. I was certain that I had friends still fighting the good fight and wasn't going to be responsible for harming a campaign that had moved on without me.

I shut off my phone and went back to bed.

The New York Times would later do a great piece on what I was chasing that night.