Weak, as Far as Weeks Go -- Pt I

January had gone by in a blur.

Chappelle came out and endorsed us. I had a host of new data friends. Our Field staff more than doubled. Andrew was cruising around the state on a seventeen day bus tour. We had hundreds of volunteers pouring into Iowa, knocking thousands of doors.

And at 950 Office Park Drive, we'd worked hard to develop our Iowa strategy and January was spent non-stop executing.

So what was the plan?

January 31st

At the tail end of December, we started taking steps to narrow our focus in the state. Iowa polling showed us in the neighborhood of 4-7% and we were well aware that if that support doubled that across the state, we'd still be short of the 15% viability threshold in each precinct.

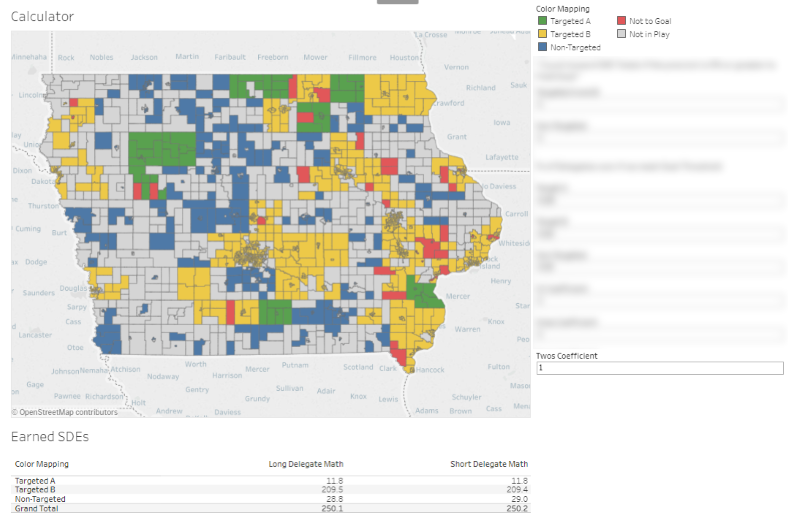

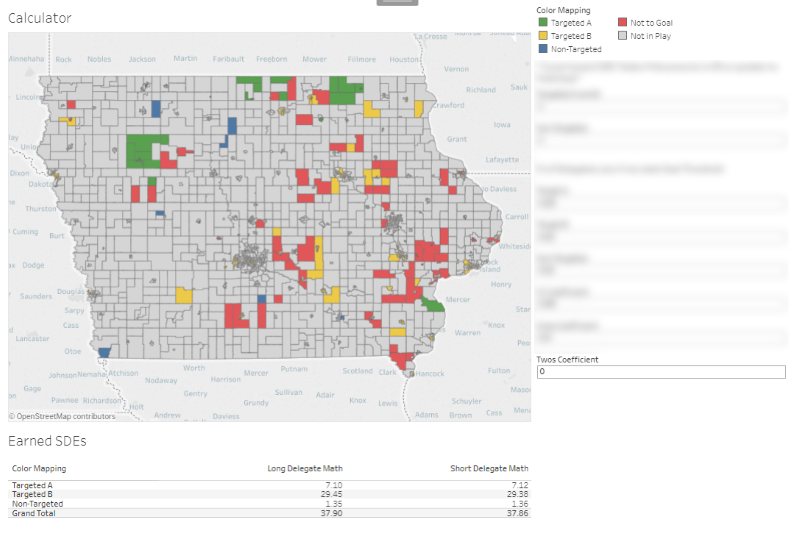

We had Direct Voter Contact data from all but a few of the counties-- some areas more than others, for sure-- but by this point, it was clear where our pockets of supporters were. The "where do we focus?" problem became a balancing act between redoubling efforts in areas where we thought we could improve, as well as expanding to areas we felt confident we'd get the most bang for our buck.

I spent a good deal of time spinning up an interactive map of all 1,682 precincts. It had everything: contact rates, supporter count, demography, historical voting patterns, volunteer presence, delegates awarded, you name it.

So naturally as soon as it was done, they asked if we could get it printed, lol

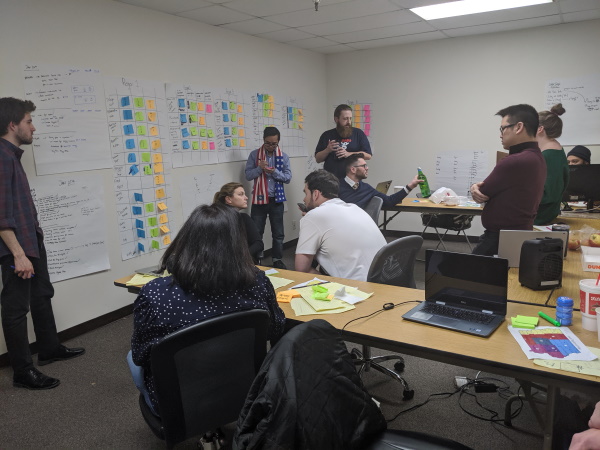

We'd cordoned off a room that was solely dedicated to answering this problem. Over the next couple of weeks, it'd house a few key stakeholders and a revolving cast of folks with broad swaths of area knowledge.

By the time we broke for the holiday, we'd come up with, in my estimation, an ambitious but comprehensive plan. Our focus areas were first determined by where we were on pace to perform well. No brainer. Then we worked out where all of the other campaigns were focusing and sought to plug gaps where there wasn't a lot of candidate saturation. Finally, we rounded out our strategy by considering narrative victories-- What areas voted Obama and then Trump? What areas had a low median income and would be greatly served by the Freedom Dividend? To have a respectable overall showing but win these areas would have given the campaign a lot of thrust going into New Hampshire.

BOB

All told, we narrowed down our focus from 99 counties to about 40. But within these counties, not every precinct was equally valueable. The number of delegates awarded roughly scaled with population, which in turn were mathed into a less-intelligible State Delegate Equivalent (SDE) value. And so it was easier to earn delegates in some precincts than it was in others-- recall that nearly everywhere, you had to earn 15% of the turnout to walk away with anything. This is obviously less work on a "per person you need to convince to caucus" basis in a precinct with 50 people than 250. But then in precincts awarding a lower number of delegates, that 15% bar was adjusted accordingly. For example, if there was only one delegate up for grabs, you needed at least half of that precinct's turnout to win anything.

As we rolled into January, we'd pared down the Iowa field plan to about 10 precincts per organizer. But "What's the next best thing for me to do?" was an ever-changing problem. Which is why we made BOB. More accurately, we made a tool to answer this question and when we couldn't land on a name for it, our main stakeholder arbitrarily christened it "BOB." This turned out to be a stroke of brilliance. BOB wasn't a clever acronym-- nor did we back into one post-facto-- but the simplicity of the name gave it better branding than anything else we would have come up with, for sure. Everyone had heard of BOB and it was a comically-easy name to remember. "BOB it" became a verb when someone was at a crossroads of decision-making (just BOB it!). Workshopping the branding brought the data team closer together.

I'm intentionally light on the specifics here, but BOB was an engine that would update every morning having crunched the production numbers from the day before. After it digested the new data, it would work through a bunch of algebra and deliver a stack rank of our day's priorities. We had a wealth of information on people who'd committed to caucus for us, people who had Andrew as their first choice, second, etc. Using this, and our supports' address info from VAN, we had an estimate for how many people we expected to show up at each precinct. Moreover, we'd modeled out what we thought overall turnout would be in every precinct and working from this, knew how many more people we'd need, if we wanted to clear the next delegate threshold (to a margin of error).

BOB would serve a stack rank of a hybrid metric of "how close to the next delegate earned are we?" and "how many SDE's would that be worth?" as well as a whole host of model scores, summary statistics, and other pertinent, human-intuition information we could use before we blindly followed a spreadsheet every day.

For instance, precincts in urban areas tended to have a high SDE weight, per delegate. If we were only a couple of "weighted supporters" away from earning another delegate there, we'd steer our volunteers to canvass those areas. They come back with, say, five fresh commits to caucus, pushing us over the "next earned delegate" threshold. And so the next morning, when BOB refreshes, this precinct is now low on the list-- it'd take another thirty-something supporters to get to the next delegate and a new priority has bubbled up.

And that was the plan. On the macro level, use the wealth of data we've collected, staffing headcount by location, and scenario testing to narrow down Iowa to the locations we thought we had the best shot. Then on the micro scale, methodically nickel and dime our way to success by constantly working the next-most-important thing.

A Critical Assumption

Of course, you probably had a couple alarm bells going off in your head reading that.

A model is only as good as the underlying assumptions it was built with and we had two big ones:

- How many supporters we'd need to hit the next "earned delegate threshold" is based on a percentage of an overall precinct turnout we don't know yet. Thankfully, the precinct-level turnout model that we used to math this out was pretty good, considering no ground truth to model off of. We over-predicted the statewide turnout by about 6%, but weren't caught sleeping at the wheel, dramatically over/under predicting at the precinct-level.

- More crucially, we were operating off of a "weighted support score" that was a linear combination of (some coefficient

A) * (number of caucus commits) + (some coefficientB) * (people rank Andrew as their number one) + (some coefficientC) * (people who rank Andrew second)

The counts for 1/2/Commits were amassed over a year of field work. We didn't do any sort of "weight by response recency" or "discount by who their first choice was if they had Andrew as a two." It was a straight-forward weighted sum, done at the precinct level. The prioritization engine we'd built was based on how these sums were shaping up across the state, day over day. Going into the Caucus, we were getting a barrage of "so how are we going to do?" questions, and so we built out a scenario calculator to stress-test our assumptions.

Essentially, it took our overall turnout projections and current supporter counts as a given. Then, whoever was looking at the dashboard, could input the "% of our 1s/2s/Caucus Commits that will show up"-- both in Target Precincts and elsewhere. On the backend, this would give us an anticipated number of delegates earned, automatically converting to SDEs and aggregating accordingly.

But this is all a bit convoluted, so I'll borrow a contrived example with nice, round numbers to divvy up the 2,107 SDEs across the state:

- In a precinct that awards 40 delegates, we think that 100 people show up in total.

- Using our calculation of (

A* Caucus Commits) + (B* Ones) + (C* Twos), we think that 20 people will show up for us. - Thus, we follow the formula (Yang Turnout * Total Delegates / Total Turnout) and expect to win (20 * 40 / 100) = 8 SDEs

- But what if we had more people turn out for us?

- 21 -> (21 * 40 / 100) = 8.4. Round down to 8.

- 22 -> (22 * 40 / 100) = 8.8. Round down to 8.

- 23 -> (23 * 40 / 100) = 9.2. Round down to 9.

- So the difference between 20 and 23 people means a pickup of another SDE. Lets say that our (

A) * (Caucus Commits) + (B) * (Ones) is constant at 12. Then maybe we had 80 people say they ranked Andrew as a 2 and we think 10% of them will come out for us. That's 12 + (.1) * 80 = 20. - But watch what happens when we think 2's like us just 5% more

- 12 + (.15) * 80 = 24

- (24 * 40 / 100) = 9.6. Round down to 9. Extra SDE.

Play this out across the other 1,681 precincts and a couple percent-point changes in your assumptions echo to huge shifts in overall SDE counts. When we repeated this exercise on real data-- taking overall turnout estimates as a given, holding the coefficients for Caucus Commits (A) and Ones (B) constant, and adjusting how much weight we'd credit a Two-- it became obvious just how volatile this race was.

Keeping A and B at their modest levels, in the wild event that everyone who had Andrew as their Number Two turned out for us, we could have had a big night, depending on who we pulled support away from.

On the other hand, if nobody came around, it'd be a different story.

And what a gut-punch that was. We knew that statistically, the majority of our supporter base weren't likely to show up to caucus. But nevertheless, seeing the "Ones, Twos, Commits" numbers roll in and the crazy engagement levels on the digital end, we were always tempering ourselves against the draw of blatant confirmation bias. So naturally, there was a ton of contention over what A, B, and C values were realistic. We got it wrong, but it wasn't for lack of trying.

We looked at conversion rates when we called Twos attempting to make them Ones. Did a bunch of data munging to figure out how many of our supporters had other registered voters at the home and extrapolated. When our national texting volunteers would blanket an area we hadn't done much Field work, we'd analyze the survey responses to get a pulse on "latent support." Couple all of this with the amount of "gut" and how much we heard "when you work on enough campaigns..." and "our media buys will supplement this" we accepted that our time was better spent executing than arguing. After all, even with the tidal wave of numbers we were putting up in January, we still only canvassed like 10% of the state throughout the course of the campaign-- we weren't p-hacking in blind optimism, the margin of error was just insane.

I don't think it's constructive for me to share what our exact numbers were. But suffice it to say, after I went back and modeled the coefficients using the real turnout numbers, we'd over-predicted our support. It's been nearly a month since the dust settled and looking at this now-- besides being the ultimate fodder for "look at how different this could play out if we had Ranked Choice voting"-- I'm still torn on whether we made the right move or not. I've been thinking a lot lately about the ground truth of how many people we could have theoretically gotten if we did everything perfectly. I can't say for certain that we'd have been better served narrowing down to 20 counties instead of 40, nor do I know if given another shot I'd over-correct with pessimism.

More constructively, the next time we do this, I have no intention of waiting until November to get involved. There was so much more we could have done in the digital space, as well as setting up a better data pipeline to calibrate our estimations as more information rolls in. Regardless, we neither had the gift of hindsight nor time to turn every stone by the time February rolled around. The train had left the station and there was still work to be done with the hand we'd dealt ourselves.

February First

There's an interesting phenomenon that happens in the days leading up to the caucus. I mentioned before how adaptive everyone was, constantly task and role-switching to do the next best thing for the campaign, but as the countdown goes from weeks to days to hours, that pool of "things that need doing" gets smaller and smaller.

And Now We Wait

By the end of January, "just get people to turn out and vote" became priority number one for virtually everyone.

This meant spending the weekend beforehand preparing all of the paper materials that our volunteers would need to do one last door-knocking push, should VAN go down.

After that was done, it was a flurry of placing all of the volunteer Precinct Captains that we'd amassed over the past few months. Coordinating registration between volunteers, the campaign, and the hundreds of precinct chairs became a full-time job for a handful of people. Then we backfilled every targeted precinct we hadn't filled yet with a staffer from Iowa HQ. That weekend, damn-near every laptop screen that I passed by had VAN opened up, as everyone dialed down the list of known supporters in their precincts. Introverts practiced their ninety second Caucus Night speeches, everyone drilled "worst case scenario" procedures, we double and triple checked caucus locations.

Pivot

Meanwhile, the data team was done with precinct targeting and there really wasn't any new information coming in from Iowa.

Everyone back in HQ pivoted, adapting BOB to all of the other early states. This largely amounted to refactoring the codebase and training folks in the tools. The code work meant generalization, find/replacing 'IA' a bunch of times, handling timezone stuff, etc, but I'd be remiss if I didn't shout out the work they did on brand-extension. Most notably, Nevada's instance became "Blackjack BOB" which took the "BOB" moniker from good to great, in my estimation.

Additionally, our tech team had built out a Caucus Night SlackBot, designed to help collect data, guide our Precinct Captains through the procedure, and outline some optimal strategy information. However, the app had run into a series of bugs when we tried beta-testing in the run-up to the big night. Robin and Louisa moved over to help QA and bugfix, as did Andy and a few others. I'm not entirely sure that any of them slept those last 72 hours.

Finally, Troy and I sat down to build a suite of dashboards that we'd use to watch the Caucus data roll in. We wanted to know how the night was shaping up for every candidate, how things progressed from First Alignment to Second Alignment, how we were faring in the areas that we'd targeted, where we'd won anything outright, all of it. And as soon as we possibly could. Also, we want this for both the offical IDP data as well as the SlackBot data when it comes in.

If you're at all familiar with Tableau and how all the caucus math is calculated, you might be thinking to yourself "that sounds like Level-of-Detail calculation hell." And you'd be right. Sincerely don't think I could have done it without Troy co-piloting and keeping my head on straight.

February Second

The day before showtime, everyone was locked in.

A "placing precinct captains" team had grown to about a dozen and they were making hundreds of confirmation calls all day. The SlackBot crew spent the day stress testing and putting the finishing touches on the app. Troy and I used the data schemas from each source to mock dummy datasets and practice doing analysis on the fly. I guess there was a football game on TV or something? idk

We had an 8 AM call time the next morning and most of the office had cleared out before midnight. That was it. Three months in this office and we'd left it all on the metaphorical field.

The room where we'd housed our daily stand-ups had gone from a dozen

to about twice that

to nothing.

A week prior, our non-descript conference room became the War Room.

A few days after that, it was again repurposed as a central hub for all things Get out the Caucus.

Then it, too, was bare.

I went back to my AirBnb, got a nervous night's sleep, and got ready for the real thing.

But more on this next time.

Cheers,

-Nick