I Had the Data -- Pt I

After I'd taken the job, I was getting messages left and right from friends, family, and former co-workers. A good deal of it to the tune of: "Wow. You work for the #MATH campaign. You guys must be doing some crazy data stuff!"

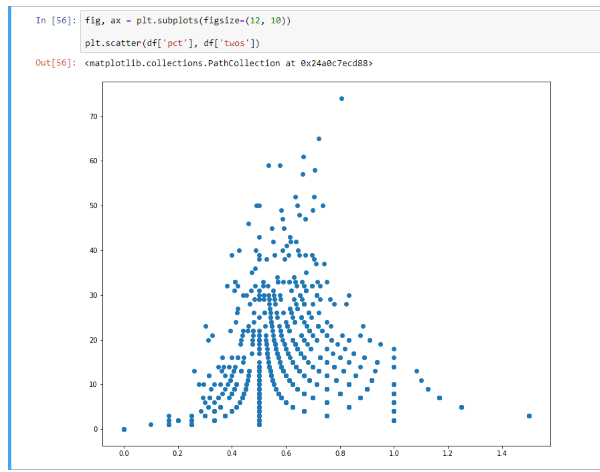

And I guess that's technically accurate, insofar as we'd built derived metric on top of derived metric and near the end were looking at very nuanced KPIs to orchestrate Iowa. For instance, this distribution occurred naturally in two of the metrics we were looking at every day.

But as far as Data Science goes, we made very pragmatic use of our Data Scientists on staff. To wit, we didn't do any sort of Deep Learning application, nor Multi-Armed Bandit problem (though the idea seemed to get thrown out there at least weekly). Which isn't to say that folks on the team didn't have the technical chops (Kris and Kevin are the realest). Nor that there wasn't an appetite for that sort of work-- I'm confident I'd heard pitches on everything from blockchain to contagion modeling by the end of my first week.

A commonly-accepted Data Science adage suggests that you spend 80% of your time on Machine Learning projects cleaning and preparing the data. And I think that this generally holds when you've got some existing familiarity with your data and the processes that generate it. Coming from industry, most of the data I touched had undergone some convenient preprocessing and documentation by hoardes of crack engineers. That wasn't exactly the case here.

It might surprise you to learn that everyone that worked on the data team was taking their first plunge into politics together. Or it might not, this campaign was pretty punk-rock. In any case, we were all light on area knowledge and for the first while, that "percentage of time spent cleaning the data" looked closer to 100.

The Data (Everyone Had)

I'm going to take a wild stab in the dark and say that if you're reading this, you've probably never worked on a data team in politics, neither. So here's a quick overview of what you can probably expect to find on any campaign.

Voter File

It all starts from the Voter File, which contains a record of every person registered to vote in a given state. Additionally, it has information regarding historical election participation, addresses, contact information, age, sex, nicknames (you bet your ass I gave my friends back home funny nonsense names. Sorry, not sorry "Big Gravy").

As people registered to vote, or updated their existing registrations, the database would adjust accordingly. And this fed into a platform called...

VAN

So VAN (Voter Activation Network, I think. Too proud to Google this one) is a database that takes the Voter File and then, for a nominal fee, gives each campaign access to affix their own data to it (e.g. survey responses, event attendance, contact history). I think most or all of the Democratic campaigns use it. It's run by a company literally named after an individual, so you know it's the tool of the people. See also: paying a company called Shadow to build a slick app that ensures there won't be another Iowa Caucus.

There's also a tool called Nation Builder, which I'm told does a lot of the same things that VAN does, but I never had any exposure to it.

Anyhow, wrapped around VAN, is a web-application layer called VoteBuilder. Which I did have to Google this time, because we always just called the whole thing "VAN." Everyone, from campaign staffer to volunteer, had access to our campaign's instance of VoteBuilder and it was the primary data-capture mechanism when doing intentional Direct Voter Contact.

Volunteers that wanted to come into a field office and start making calls to voters would do so via VAN. Conversely, the army of wonderful, crazy people that braved a blisteringly cold Iowa winter to knock doors would instead use...

miniVAN

Before I start in on miniVAN, let me just say that this was 10/10 branding. As we'll see in a minute, the data ecosystem is a complicated tangle of data handoffs, licenses, terms, and names, but add in the fact that they called the companion mobile app to VAN "miniVAN" and on average, they're nailing it.

Essentially, miniVAN was a tool that provided a map of who to talk to, as well as a data capture interface. But before someone could utilize it, a staff member would go into VAN and:

- Pare down a population of people to talk to from the voter file

- Open up a map showing a subset of that population, all within the same general area

- Use a really neat interface to "cut turf," essentially sectioning off enough homes a person could reasonably visit within the span of a shift

These turfs would have a corresponding code that mapped to the addresses they contained. This allowed a volunteer to download the miniVAN app, log in using the campaign credentials created by their organizer, punch in this code, and go.

As they walked, they had access to some basic household information as well as any notes someone had entered (there was a lot of opportunity here for data-driven conversation priming that we never prioritized working on). Then, depending on how the conversations went-- if they even happened at all-- the volunteer would mark the status of the canvass attempt (canvassed, not home, hostile, etc) as well as fill out any relevant survey information.

This would flow back to their organizer for some spot checking/manual data validation, who would then commit the data back to VAN.

MyV vs MyC

On the VAN (VoteBuilder. Had to catch myself.) side, the data was organized into two halves:

- MyVoter. This was based on a direct import of the state voter file. Some 2-point-something million records in the state of Iowa. Most of the address/contact information was shared campaign to campaign, but we also had info on our interactions with them-- contact history, survey responses, etc.

- MyCampaign. This was the half where you'd go to find information on our supporters. These were people who'd responded positively to certain survey questions, who'd volunteered, attended events, and various other criteria.

They were separated into two distinct tabs when you'd open up VAN.

For the most part, we orchestrated Direct Voter Contact in the MyVoter half. This is where you spent most of your time if you were a volunteer, trying to find voters to migrate over to the MyC side. Organizers, on the other hand, would use MyCampaign to recruit volunteer shifts and coordinate event invitations to supporters. Of course, when we spent the last couple weeks in Iowa in "Get out the Vote/Caucus" mode, we were reaching back out to supporters on the MyCampaign side, to ensure that they intended to come out and caucus for us.

It took a lot of knowhow (not to mention appropriate permissions levels), but VAN also had a lot of handy tools to cut down the timely, manual use of the interface. We made good use of saved searches to build consistent populations to contact, the event scheduler to assign people to volunteer shifts, and before I'd arrived, an array of self-serve reporting tools.

Phoenix

Everything Field did was out of VAN, which in turn meant that the data to facilitate everything Field did was in VAN. Sort of.

As best I understand it, the DNC had the voter file, VAN licensed its use and all of the campaigns used VAN, getting updated voter file data at some periodic cadence. Then, at like a nightly clip, VAN would take all of the user activity generated in a day and kick all of the underlying tables to the DNC. Finally, the DNC organized all of this information into data schemas on a BigQuery platform called Phoenix.

And they had a whole tech team staffed to support this corner of the data ecosystem, complete with product owners and road maps. They'd scheduled a standing meeting with the Yang data team where they'd foreshadow things like new market-segmentation models or data deprecation timelines. I went to the first couple, but quickly stopped attending as I got busier and busier trying to organize the fundamentals in Iowa-- it felt akin to sitting around talking about the pros and cons of various luxury features for a car that had yet to recieve an engine.

I don't think this was indicative of anything either of us were doing wrong, mind you. There was always the opportunity to introduce questions or concerns to the top of the meeting agenda, which I almost never utilized. Instead, I made liberal use of shooting every single question I had to tech-community@dnc.org-- north of a dozen times a week, easy. Their responses were always timely and more-often-than-not what I needed to get unstuck.

Additionally, they had a good deal of documentation scattered across a shared Google Drive. But even this seemed geared to an audience already familiar with how everything operated. Moreover, you had to know where to look, if it existed at all.

For instance, a human being in VAN can have a record in MyVoter with a unique ID. They can also have a record in MyCampaign with an ID, unique per state. They can also have a unique person_id that didn't directly correspond to either MyV or MyC. A person could have one of the three, two of the three, sometimes even three and it was never obvious why. We never found any documentation spelling out how these IDs came to be and would talk ourselves in circles trying to figure it out. This was an area in particular where questions to the support queue didn't bear a lot of fruit. Nor did looking for help elsewhere.

But perhaps I've spent the last handful of years spoiled by StackOverflow and the Python community....

Civis

After the DNC took the tables from VAN and pushed them to Phoenix, we had a vendor called Civis that would ingest everything into their RedShift instance for us to work out of.

This afforded us a lot of things. Chiefly, it meant having a place to sink all of the other, non-VAN, non-DNC data that we were generating. It also gave us a platform to host Tableau dashboards on and-- in my estimation it's best feature-- the ability to create and orchestrate scheduled workflows. We used this to automate... lots of Google Sheets that would have otherwise been the morning chore of some organizer futzing with a VAN extract every day.

Of course, using this feature to try and match the reports that VAN would generate was predictated on being able to reverse-engineer what VAN was doing. Almost always easier said than done. I was reminded of an XKCD comic every time I had to tell someone I couldn't help them out.

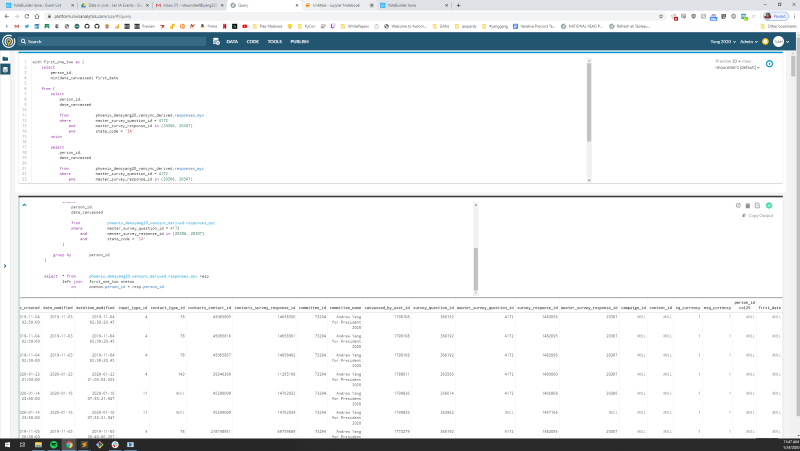

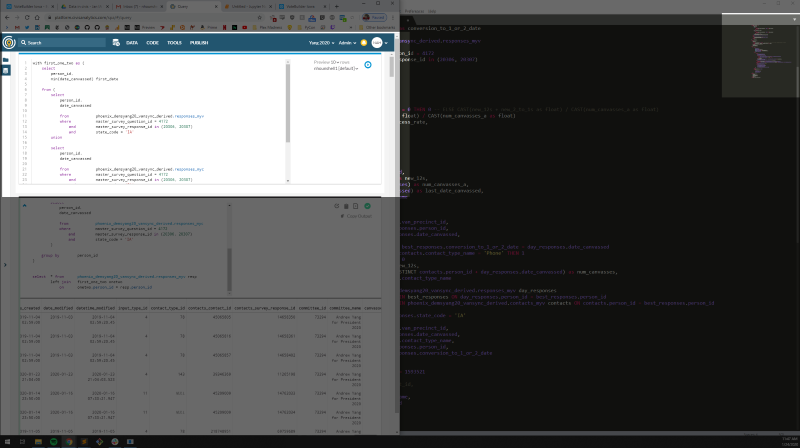

As far as criticisms of Civis go, the majority of my gripes were UX-based and not worth enumerating. On the other hand-- to the absolute shock of none of the Data team-- I'm happy to die on the "SQL interface" hill. Now, I've done 99% of the SQL in my career using SSMS-- a real feature-rich IDE supported by Microsoft-- so I'm certain my expectations are warped. But it drove me up a wall to spend the majority of my time typing in a terminal that took up less than half of my screen, maximized.

This was fine if I was writing something less than 25 lines

But that was almost never the case.

Working out of a text editor meant foregoing Intellisense, so many of us just memorized the tables and fields we wanted to use then copy/pasted the code into Civis when we were done. But I digress.

In terms of features, I'll level the same criticism of Civis as I have every other "One Stop Shop Data Science Platform" I've ever worked on: To operate with a good data science workflow you need:

- Robust GitHub integration

- The ability to organize projects into directory structures like these

proj

|

| analysis.ipynb

| queries/

|

| population.sql

| utils/

|

| data_processing.py

| viz.py

- A centralized location (ideally a package index) to house the Python code you wish to reuse

Instead, we wound up developing with a myriad of anti-patterns that I won't bore you with.

But to walk it back a minute, these tools-- Civis, Phoenix, or otherwise-- are all relatively new in the political sphere. In general, tech and politics doesn't attract the kind of money needed to develop state of the art platforms like you'd find at, say, Amazon, Facebook, or Capital One. Additionally, I came to learn that there are only a small handful of vendors that are DNC-sanctioned to even house the data. All told, I think Civis is a decent tool, though I honestly have no idea what the other options were, nor how it compared to them. The decision for the campaign to go with Civis happened long before my time and in truth, is one of my biggest question marks should I ever consider doing all of this again, but at a campaign's inception.

And that's the long and skinny as far as tooling goes. I'd wager that everything I've listed above would be practically one-to-one transferrable knowledge for any other campaign. Next time, we'll talk about what else we had, and some of the nuance of using that data.

Cheers,

-Nick