The Right Tool for ̶t̶h̶e̶ Any Job

I'm sure we've all heard the "Hire a lazy person to do a job" Bill Gates quote a million times. But what does that actually mean? In the weeks leading up to and after my last post on my Daylio data, I've been thinking a lot about tools.

And this is far less about what hardware you're using when you sit down to knock something out. Nor is it a stance on the Python vs R vs whatever else debate. Instead, I want to talk a bit about the way I consider tooling as an analyst, and how that's changed over the past couple of years.

Gotta Go Fast

For starters, I should note that this video speaks to me on a very visceral level.

How often do you take the time to learn hotkeys in whatever software you use?

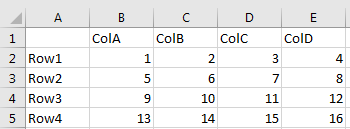

Take Excel for a example. Say you had some aggregated data in SQL or some other source, and you wanted to do some formatting to get from this

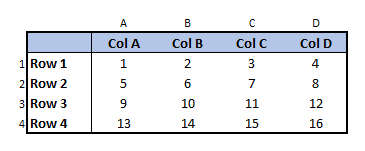

to this

If you were so inclined, you can get most of the way there by typing

Click Cell A1

CTRL + A

ALT + (H, B, T)

↑

CTRL + SHIFT + (→, →)

CTRL + B

ALT + (H, B, O)

ALT + (H, A, C)

←

CTRL + SHIFT + (↓, ↓)

CTRL + B

ALT + (H, B, R)

↓, →

CTRL + SHIFT + (↓, →)

ALT + (H, A, C)

CTRL + (←, ↑, ←, ↑)

ALT + (H, I, C)

ALT + (H, I, C)

ALT + (H, I, R)

ALT + (H, I, R)

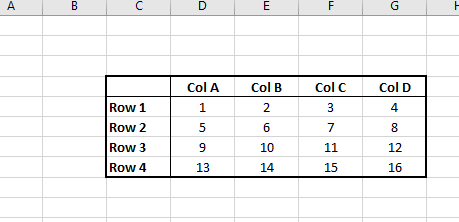

Which gives you

then it's just labeling the rows/columns with the headers, sizing them appropriately, turning gridlines off, and shading the cells on the top. Not moving mountains here, but if you're quick enough, you're probably saving yourself 30s or so per figure. (Found these links invaluable getting started in SQL Server Management Studio and Sublime Text. Hopefully they're helpful for you too.)

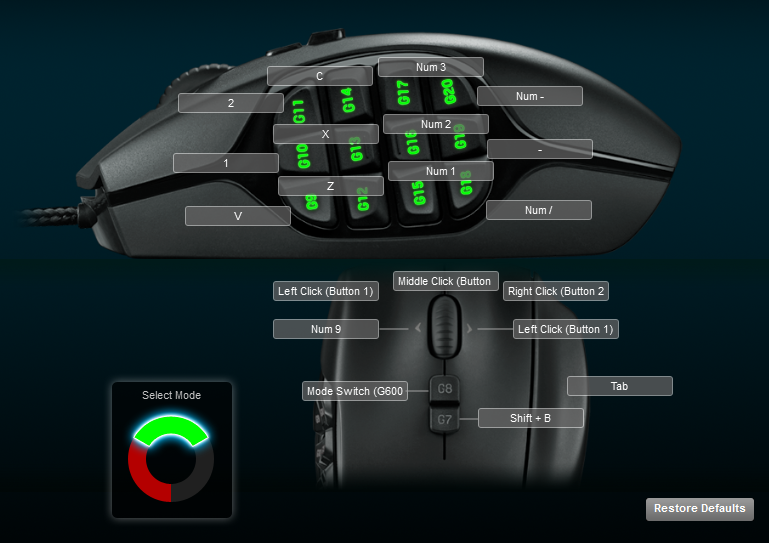

Of course, getting comfortable with the right keys isn't anything new. If I'm firing up a new game that has more than like 6 action keys, you'd better believe that I'm spending the first hour or so running in circles and rebinding actions to my superfluous neckbeard mouse until I'm comfortable enough that I'm not deliberately thinking about which keys I'm pressing.

And the benefits of learning how to navigate with your key bindings aren't unique to just the programs themselves. For example, on Windows:

- If you ever find yourself wanting to save a copy of something, more often than not, ALT + (F, A, B) will get you to a "Save file as" prompt

- Windows + E opens the file explorer (where you've already bookmarked the directories that you popularly used, no doubt)

- A quick ALT + TAB returns you to the last window you were working in, which holding ALT allows you to navigate between windows with your arrow keys.

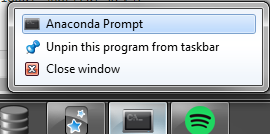

I'm confident that not all of these were news. But what about the global shortcut keys? Say you have a program that you often find yourself wanting to open quickly. Right-clickit

then right-click the name of the program itself, and select Properties. That'll take you to a prompt that looks like this.

Where you can set the "Shortcut Key" field to be whatever you want. I usually opt to make mine some derivation of "CTRL + ALT + SHIFT" and then some random character. This means that when I'm on a tear and want to get to some kind of tool, it's a keystroke, not some point-and-click away. Off the cuff, I do this for:

- Snipping Tool: X

- Python: P

- Sublime Text Editor: S

- SQL Server Management Studio: Q

- Git Bash: G

- Calculator: C

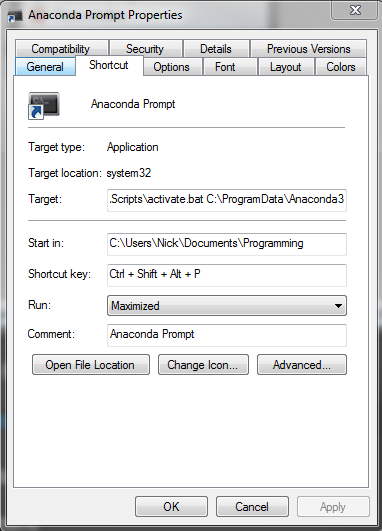

In addition to learning hotkeys, I use this cool desktop utility called Always On Top which allows you to keep windows you're not actively working on in the forefront of your screen, letting you do stuff like

Of course, just because you're faster doesn't necessarily mean you're better. If you get into the habit of just going as fast as your APM will allow, it's probable that you'll find yourself in a situation like this.

A 3 hr coding tear later:

— Nick (@NapsterInBlue) August 30, 2017

Pro: Managed to get a working data pipeline

Con: I've looked forward to hangovers more than I am the refactoring

Spoiler alert: It was a ridiculous pain in the ass opening up the repository and trying to figure out what I had done, days later.

Which transitions nicely into my next section.

Slowing the Hell Down

To Save Time

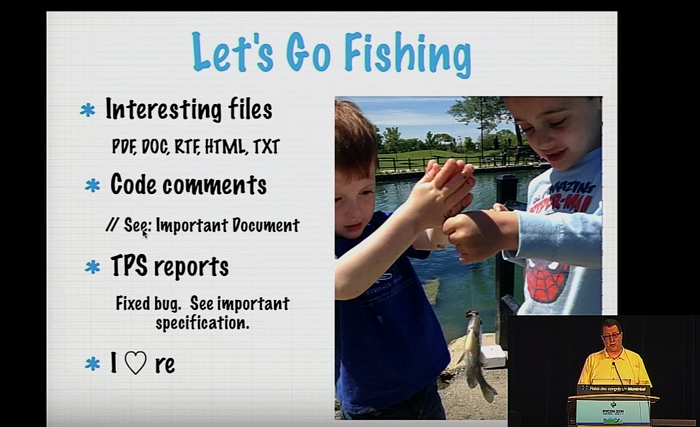

I've been gradually digging through the old PyCon archives the past couple weeks. One of my better finds was a talk where a guy was locked in a vault with hundreds of boxes containing printouts of source code and a computer with over a TB of poorly-labelled files and no Internet connection. He was an expert witness in a tech patent case and heavily utilized Python to help him organize and detangle the mess he was parked next to. Before he went heads down and threw himself at the mountain of work to make sense of in front of him, he first took a few weeks to-- this killed me-- reimplement Git and Unix commands from scratch using vanilla Python 2.7, to assist in all of the parsing and cataloging of the information on this computer.

The talk is fascinating and absolutely worth the bookmark, but as it relates to this section header, it perfectly illustrates the kind of measured approach that I'm advocating for here. When faced with a problem that he could have, for sure, just started in on, he paused and assessed what tools would make his research go smoother. Even if he pushed himself to the absolute limit, there's no way that he'd be able to perform the complicated searching needed as well as a computer did, so instead he figured out what sorts of things he'd need to do, and set computer up to do it for him.

And sure, by doing this, he saves himself a ton of headache. But the thing that's most exciting to me is that by setting himself up this way, he's minimized the amount of time it takes him to go from good idea to execution. As soon as he had an idea about how to explore the code, he could just hop in and do it.

To Save Brain Power

Consider the earlier Excel example. If I got blisteringly fast at the muscle memory needed to go from raw data table to 2/3 of the way to something neatly formatted, it'd still be orders of magnitude slower than how fast a computer would be able to do it. Instead, maybe I take an hour and knock out a Macro in VBA-- or better yet, build a Python function with a call that looks like export_pretty_table(data, fpath, headerColor) because even if it's only saving you ones of minutes, it's still "costs" you a non-zero amount of your brainspace to make sure that you're checking all of the boxes correctly, and that's probably nobody's favorite part of the analysis.

I've spent a ton of time in the past few weeks thinking about this in particular. Had a handful of ideas about some broad, multi-movie analyses that I'd like to do that could really benefit from having some numbers behind the observations. All kinds of things from box office data to the number of theaters they were showing in to composite review scores. All of this data exists on one form or another across the Internet. But is it a better use of my time to get at this as I need it? Or will I thank myself later for taking the time to build a handful of robust scrapers that will get me the data as soon as I've got a good idea for a post, and take off from there?

Pretty excited to have a few of these nearing completion, by the by.

To Share an Approach

What about the analysis approaches themselves? By happenstance, in my time with QL, I've supported a handful of different business areas. In so doing, I started to see the patterns in the types of analyses we do, like classes of problems-- that if you listed out all of the steps beyond "collect the area-specific data," you'd see a good deal of overlap, regardless of whatever data you happened to be a SME in. A typical conversion problem behaves like a typical conversion problem; understanding how to tie together dimensionalized data will make learning every new dataset that much easier.

How about a super-generic example?

Say you own a supermarket and want to understand the flow of customer traffic through the shop over time. And so you give a few teenagers summer jobs to park themselves in front of the aisles and write down:

- What aisle the customer is walking down?

- What time they entered the aisle?

- What number they're wearing around their neck? (Oh yeah. Assume this is a weird dystopia where this is pretty normal, lol)

Okay, so what sorts of things can you glean from this?

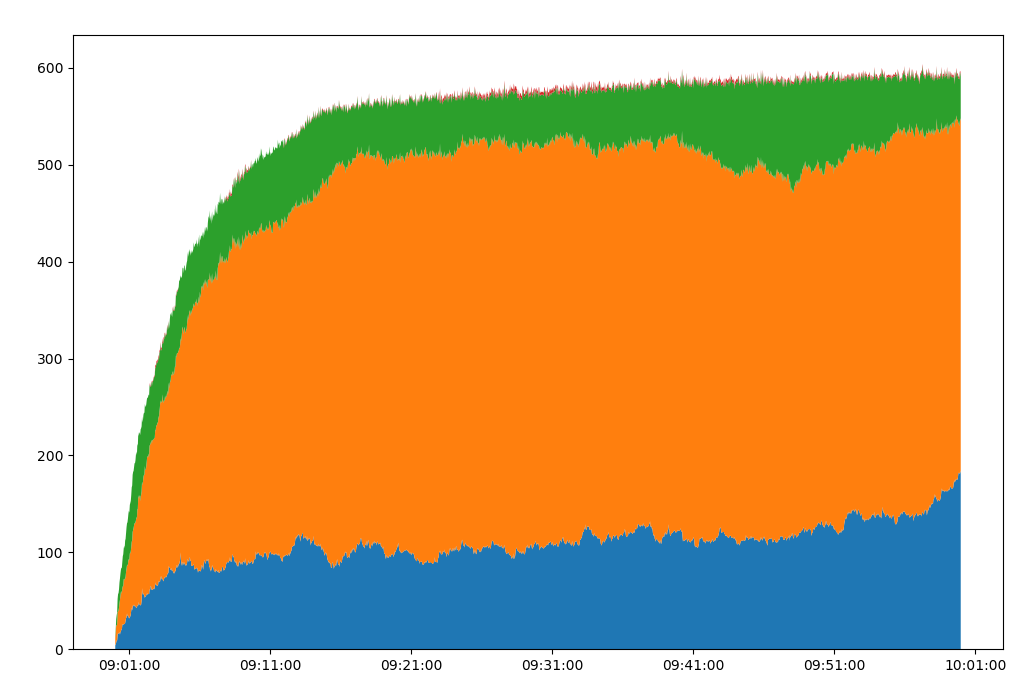

Well, if you're creative, there's a messy dataset join that you can get at that would allow you to say "At this specific point in time, how many people were where?" Which is cool. You can throw that against any sort of time-specific metric you've got, from cleanups needed to figuring out when you should focus on restocking specific aisles in the store. You run that on enough different samples across time and you can start to see patterns, and enrich your understanding with visuals like this (different area colors represent the different aisles)

Obviously not going into the specifics, but it's not tough to imagine a use case for something like this for an analyst at a mortgage company. But that's the thing-- it's easy to think of a bunch of problems that fit this form. And to do all of the data processing/joining on the SQL side means that you'll find yourself copy/pasting, and subsequently modifying, the same chunk of code into whatever queries that you're putting together, every single time you want to do something like this. Hope you remember everything correctly!

Instead, a few of us took the time to sit down and said "assuming a dataset that fits the form of "Agent," "Their State," and "Time Entered the State" you could use this for damn near anything. What took us, idk, 5-10 mins per cross section that we wanted to explore is now tooled down to a few seconds and is generic to whatever data you want to point it at.

To Cover Your Ass

And I haven't even brought up correctness. There is, after all, an positive relationship between the number of errors and the amount of human entries. Something as simple as table formatting might not be the most perilous part of your day, but what about data cleaning? There's this ubiquitous notion in the data science community that 80% of any analysis is spent doing data prep-- a problem that's only growing as the amount of data sources of all shapes and sizes continues to swell. This is where formalizing data definitions and sharing SQL views and map/cleaner code becomes invaluable.

This extends to the ability to share your work, or understand the work that you did before. It's not a tangible tool, sure, but pausing when you're done writing something that works to document it for the next person in line (yourself or otherwise) is just as, if not more, valuable as any hotkeys or software. If I'm digging through some old code that I wrote where I stuffed 40 fields into a table called #temp, I set Future-Nick's lockjaw to flare up due to excessive teeth grinding. Instead, if I'm skimming through a query and can scan through the intermediate tables that I'm seeing:

#PilotLoans#ClientsOnLoans#TeamMembersThatTouchedLoans#CallsFromTMToClient#PilotLoans30sOrLonger

Regardless of whether or not I understand all of the underlying data or all of the exclusionary logic at each step, I can piece together the general approach of the couple hundred lines of SQL, and know where to focus if I'm concerned that anything is incorrect in my comically nondescript example.

Much better than (true story)

#meeearp#butts#temp#tmp#meeeearp#lololol

yeah?

So When and Where?

At this point, maybe you see the value of stopping and figuring out how to work better. I know I did.

In my last transition from one business area to another, I took the opportunity to shotgun a bunch of Git knowledge and start compiling a wiki to chronicle everything new that I was learning. It was enormously helpful for my own understanding to document all of the new information that I was hearing, and hey, it was occasionally useful to the folks around me.

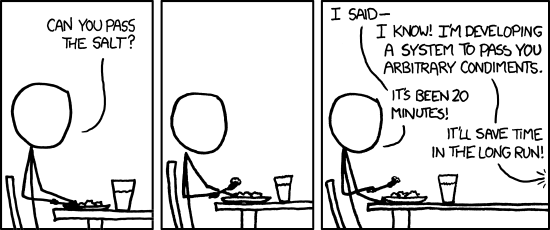

But I'm also more-than-acutely aware that at glance, it might appear as if this is the only mode that I operate:

And in truth, this is something that I'm actively working on. I hardly think that I'm bullet-proof in this regard. Like anything, to shackle yourself to an absolute approach is to set yourself up to miss the mark, and flounder spectacularly doing so. So how do I strike a balance between tooling up and, well, actually doing anything?

That question's been on my mind a lot the past couple of weeks. To paraphrase: "How do you know when it's a good time to focus on tooling?"

Ate lunch this afternoon watching another really great talk worth bookmarking by Brandon Rhodes. Among many other things, he touches on 3 big points I want to address.

- "Many novice programmers have no gauge on whether the tools they're using are wasting their time."

- This one rang true to me in a big way. If the only tool that you know exists is Excel, then watching someone else do your job quickly and with a fraction of the effort in SQL or Python is going to blow your mind.

- Similarly, if you know a tool well enough, but haven't seen how someone else uses it, you're bound to pick up a best practice or two just watching them. Hell, just this week someone turned me onto the LEAD/LAG functions in SQL and I was near hysterical that I could finally let the ridiculous ROW_NUMBER PARTITION BY into self-join fall out of my head.

- All of this to say, beyond the obvious project correctness and knowledge-redundancy that paired programming creates, learning the different ways that someone operates can dramatically improve your perspective when approaching problems.

- Frustration as a motivator

- One of the easiest heuristics I've heard about all of this tooling business is "if you have to do it more than twice, find a way to automate it."

- This way, you don't find yourself burning untold minutes and brain cells doing the same repetitive tasks, and can instead wrestle with the problem at a more stimulating level. Love this.

- As Rhodes said, "If it feels like I'm flailing, then I stop and work on my tools."

- I'm only just figuring out how to break an awful habit of mine. Maybe this'll sound familiar:

- Working between my text editor and terminal and I'm trying to debug a very specific bit of behavior in a class I'm working on. My last 4 IPython commands look like:

[1] run exampleclass.py [2] data = get_data_from_path('filepath') [3] test = ExampleClass(data) [4] test.method_im_debugging()

- Working between my text editor and terminal and I'm trying to debug a very specific bit of behavior in a class I'm working on. My last 4 IPython commands look like:

- It's just a quick fix. Should only take a run or two.

- And so 30 runs later, I'm not much closer to a solution, and now my workflow has gone from deliberate to frantic, spending time and energy cycling through the history of previous commands.

Tinker and make changes to exampleclass.py ↑, ↑, ↑, ↑, ENTER ↑, ↑, ↑, ↑, ENTER ↑, ↑, ↑, ↑, ENTER ↑, ↑, ↑, ↑, ENTER Damn. - That time and effort adds up. And if you're chaining together more than a few commands this way, you can find yourself in a needless cadence of muscle-memory and frustration from all of the repetition.

- Instead, now I don't do any development without this gorgeous if block at the bottom of my scripts.

python if __name__ == "__main__": data = get_data_from_path('filepath') test = ExampleClass(data) test.method_im_debugging() - and my workflow looks like

Tinker and make changes to exampleclass.py ↑, ENTER Rinse, repeat. -

Then the twenty terminal keystrokes becomes two. Four calls becomes one. And it works exactly the same. Might not seem like much, but it makes a world of difference for me.

-

Traction as a motivator

- This one's interesting. Basically, human nature suggests that you're going to gravitate to doing whatever's clearest/easiest.

- However, just because something feels like the path of least resistance, doesn't mean it's the most essential thing you should be aiming yourself at.

- In fact Rhodes suggests that the part you're going to struggle with the most is precisely where you should be focusing your tooling efforts.

- I'm inclined to agree with him. Web scraping and Regex are a pain in my ass. Love the site, though I may, if there was a "how long have I been on this site?" counter for Pythex, I'm not sure I'd want to see it. But packaging them into function calls when I need to use them means that I can solve the problem once and then use the functions to get to the stuff I'm good at.

Conclusion

It's worth mentioning that I'm spending a good deal of my time lately figuring out how to navigate through the intersection of these last two points-- frustration vs traction. Historically, if I get to a spot where I don't know how to do something, or am confident that if I just knew this one library a bit better, I'd be able to write elegant, effective code to knock out whatever I'm stuck on.

However, as I'm learning more about software architecture, specifically SOLID coding principles (wearing an Econ background on my sleeve here, citing something so basic), I'm having an easier time just building something that works, if barely. If I chain together a bunch of method calls, each of which are technically correct but are revolting under the hood from a design or library use perspective, then getting something that works allows me to confidently iterate on the parts that aren't so great. Like so:

compare_two_movies(movie1, movie2):

|

---> check_for_cached_data() # basically my Dayilo stuff

|

---> scrape_box_office_data() # finally works

|

---> scrape_rating_data() # finally works

|

---> normalize_data() # technically works. Probably better Pandas methods I could be using.

|

---> make_relevant_plots()

|

---> plot_gross_over_time()

|

---> plot_num_theaters_over_time()

|

---> # room for more visuals

|

---> cache_data() # basically my Dayilo stuff

But hey, it works. All of the things I'd do to analyze the differences between two movies are tucked away into a repeatable function call.

And then from there, I can start to explore all kinds of development patterns and testing strategies and other things that that are showing up more and more in my google searches. But that only happened, interestingly, after I dramatically sped up the way that I worked, and then saw the value in then slowing it back down by a whole lot.

So in summary: Get fast enough that being slow becomes a choice. Then choose to find/build the right tools to make things easier on yourself. Might seem unintuitive at first, but in the long run, the time investment pays for itself several times over.