A Lot of Thoughts About Tech Debt

Overview

So I finally finished The Phoenix Project after chugging along on it for the better part of a month. Pulling, verbatim, from a summary paragraph at the beginning of the reference section, I'll let it explain itself better than I could:

The Phoenix Project frames how a core, chronic conflict between Development and IT Operations preordains failure for the entire IT organization, as well as the organization it serves. Left unchecked, the conflict increases time to market for Development, creates longer and more problematic deployments during feature releases, increases the number of Sev 1 outages, and IT Operations becomes increasingly buried with unplanned work, making it difficult to retire technical debt.

I picked this book up for a number of reasons-- not least of which because I see it all over the desks of our Network Operations folks as I pass to and fro to the kitchen to sate a moderate coffee habit. But I also picked it up to try and find some new perspective on what I'd characterize as a tough couple of months transitioning to a totally different business (and by extension subject-expertise) area. I'd gotten pretty good at tinkering with what I knew, but found myself unbelievably frustrated by how much effort it was taking me just to hit the bare minimum of something new. In hindsight, the good bulk of it was inevitable growing pains-- the more exposure you have in an area, the easier it becomes to take on and contextualize new information and pick good projects. Nevertheless, I struggled to reconcile knowing that there had to be a better way and not knowing how to plan/build whatever that meant.

As far as reading The Phoenix Project for reading's sake goes, the story and characters are aggressively meh. It's fraught with heavy-handed dialogue all throughout as the characters hang onto every word of the "Cool, Edgy Shareholder Dude" Erik, who ultimately winds up being equal parts Mary Sue and insufferable neckbeard. Furthermore, from a story structure perspective the story does a hard, unlikely transition in the third act (found halfway through the book...) as the cookie-cutter angry "get off my lawn with your SnapChats, I was in Korea" CEO survives a near-fatal case of whiplash from how much a sudden about face he does going from hard ass to kiss ass. He's either the stone-cold disciplinarian/villain of the story or the cool dad that lets you watch South Park when mom's gone, freeze all of your existing business engagements for a month to play tech-catch-up, and rents Mario Party 2 when your friends come hang out. When he's not clearly being used to drive the plot, he's some sort of ill-informed "for the audience" character that explains away the books issues with inaccessible manufacturing theory. Idk... I'll let the book speak for itself again

"I'd like to think that The Phoenix Project is what [similar author] would have written if he wrote [similar book], and had Tarantino or Scorsese as a novel coach."

Don't let my over-opinionatedness on the story deter you, it's always a real point of contention for me. Nevertheless, I still strongly endorse this book as there's a ton of good content in here. At a 1000 foot view, the story is about a company with an unhealthy IT team slowly transforming it into a healthy one. Quizzically, despite my griping, I can't imagine this book being useful outside of its novel structure. It very deliberately sets up the context and situations of the team before showing you the tools to solve them, thus moving onto bigger, more complicated issues. To that end, the pacing is very natural. Engaging, even.

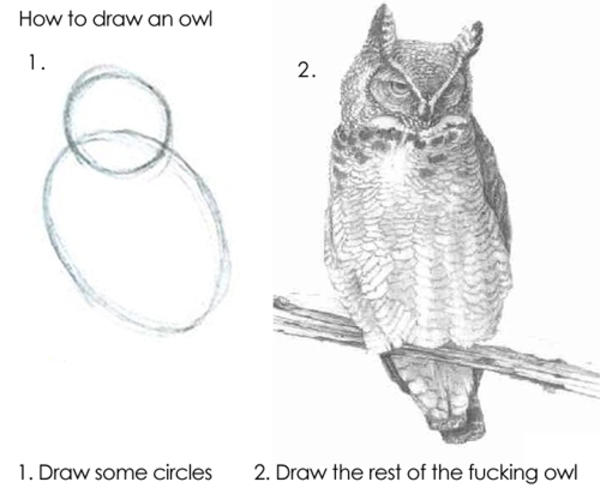

After all, you have to right the capsized boat before you can bail out the water before you plug the holes before you can sail smoothly. Without good pacing and scenario-framing, you run the risk of pulling one of these numbers.

Last pull-quote (for at least a few paragraphs...) before I launch into this

"The goal of science is to explain the largest amount of observed phenomenon with the fewest number of principles, and to reveal surprising insights."

This line is sort of out of context and is used to address a graph found in the appendix. On the whole, though, I think it instills the right mindset for approaching this book. In terms of complexity, The Phoenix Project is targeted somewhere in the wide grey area between populist reader and someone who's been in industry long enough to follow along with the buzzwords, but doesn't have the Industrial Operations Engineering or IT Architecture know-how that the book seeks to impart. There's a lot to absorb, but this blog post is my best attempt at distilling it down to the principles I got from it.

When Even the Fire is On Fire

What Got Us Here Won't Get Us There

I suppose I ought to get a couple quick definitions out of the way. The phrases "DevOps," "Development," and "Operations" appear at least seven times throughout the book (conservatively). To be about as reductive as I can, the flow of work is pretty much as follows:

- An idea originates. Typically from some meeting or initiative. Work is created.

- The Development team takes this project and does a bunch of tinkering/building until they've got some variety of application.

- They then hand it off to the Operations team who is tasked with both plugging it into the existing infrastructure as well as keeping the lights on.

- With the thing done, it makes its way to the end users, and the business monitors/strategizes around its impact.

- That's about the long and skinny of it. Business, Development, Operations, and End Users. Then near the end of the book, !!SPOILERS!! the portmanteau DevOps is, unsurprisingly, one of these numbers.

There really isn't any meaningful interaction in this story with the end users. They're basically just plot devices and shaming instruments when things go south (Think of how much you let them down! D: ). The two major conflict groups are between the Development and Operations teams and between the Business and IT-- the book describes the CEO/CIO relationship like a failed marriage where both sides feel powerless and held hostage against one another. Damn.

To better set the scene one of the characters outlines the typical breakdown of a project:

- It all starts with an urgent or immovable project deadline set by the business who ultimately does nearly none of the work.

- Pepper in some misguided "We all did our [monumentally smaller] part, you should have too." and "Perfection is the enemy of good." quotes to get my blood boiling on some Joffrey levels.

- The project ultimately spends an inordinate amount of time in the Development phase, before getting punted over to Operations at the 11th hour.

- With insufficient time to actually do their share, all critical eyes are on the Operations team as the Development folks take off, Mission Accomplished.

- What's more is that because there is no meaningful testing or quality assurance done with the project thus far, Operations is also the ones on the hook for finding and fixing mistakes.

- Like a very expensive game of Hot Potato. When the project goes over deadline, the Operations team is the one that besmirches the good reputation of the whole of IT.

- The kicker in all of this is that as a result of rushed and poorly-planned work, the business would often reject the finished and miraculously-up-to-spec product because it wasn't good enough.

And that's the world that we're dropped in. One where everyone thinks "the real way to get work done is to just do it" despite conflicting work and motivations coming from all sides. When asked how that rat's nest of ToDo's is untangled and prioritized, it's met with "[trusting] them to make the right decision... That's why we hire smart people." Woof.

So How Does This Happen?

Another definition. Throughput, similar to output, is the relationship between the speed of things going in and the speed of things going out. For instance, if I get anywhere from five to ten decent blog-post ideas a month but only wind up cranking out one every month or so, I'd consider that a low throughput. You can imagine how in a business context, this idea might lead to missed expectations and deadlines-- fortunately, I renegotiated my "one a month" goal for myself to "whenever I'd actually enjoy writing it," because hobbies, right? lol

Using this, we can examine the two biggest offenders on throughput:

- Unplanned Work. This can take the form of:

- Adhoc requests that come in high-urgency but curiously don't inform any real decision making.

- Underscoping, such as business-rule nuances that you find out on the fly, or having to rewrite whole chunks of code before you can use it.

- Anti-Work

- Could be code rollbacks due to bugs, or fixing and re-sending incorrect analysis and all of the damage control that that entails.

- These things have 0 value add. It doesn't make us better, merely less-worse.

These things happen. But (another pull-quote),

"Unplanned work has another side effect. When you spend all your time firefighting, there's little time or energy left for planning. When all you do is react, there's not enough time to do the hard mental work of figuring out whether you can accept new work. So, more projects are crammed onto the plate, with fewer cycles available to each one, which means more bad multiasking, more escalations from poor code, which mean more shortcuts... Around and around we go. It's the IT capacity death spiral."

You never want to get into the habit of impeaching the past. Decisions made in the short term may have been good ideas at the time and often simple, quick fixes are good enough. However, you should also be wary of an over-reliance these types of decisions because like the free dog, it's not the up front cost that gets you, but the maintenance costs down the road. Technical debt is a depressing mess that builds quietly. It collects like compound interest, and if you're not careful, you'll spend an inordinate amount of time and energy throwing yourself at it, not even touching the principal.

If you're fortunate enough to not find yourself on the losing end of tech debt, but are wired like me, it's still a very real possibility that you'll, ironically, spend a good deal of time worrying about it anyways. One of my very best friends described her 20s as never being sure if she's doing too much or not enough. Frankly, after two years and some change working in tech, I still find myself thinking about this quote often, if on a smaller scale.

Good news, though. This book has a ton to say on the matter, and I'm happier having read it.

Paradigms

I had a hard time outlining this section. The book juggles fleshing out two separate, but related, modes of thinking. I'll elaborate below, but ultimately, framing these two ideas as micro-vs-macro models of decision making. Essentially, you want your strongest principles to align with the Theory of Constraints which constantly refocuses your attention to the next biggest problem impeding your growth. This aggregates at a macro level to the Three Ways, which are basically graduating benchmarks of healthy workflow organization.

The Theory of Constraints

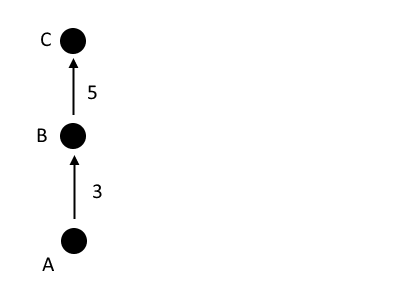

The Theory of Constraints is a based off of a book called The Goal, which I've never read but the characters in The Phoenix Project have, and they spend much of their dialogue beating a bunch of bullet points and heuristics into your head. As far as I can tell, all you really need to keep in mind is that "Improvement anywhere but the bottleneck is an illusion." I like to think about this one visually.

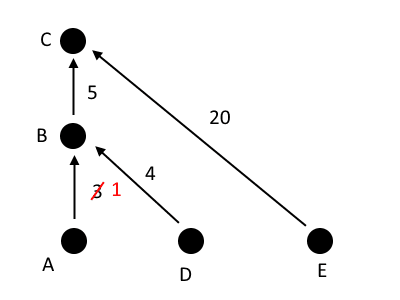

So in this simple pet example the work is finished when we go from B to C. That of course happens after the work flows from A to B. The numbers along the edge of the arrows signify how long that work actually takes. Thus, summing them up, you get 3 + 5 = 8 units of time until you're one.

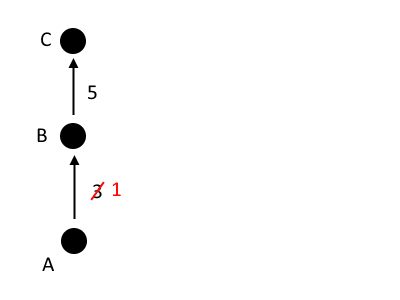

If we wanted to improve the overall time it took to finish the work, we might consider making process improvements to shorten the time it takes for either of the legs to be completed. Here, reducing AB to 1, our overall time goes from 8 to 6.

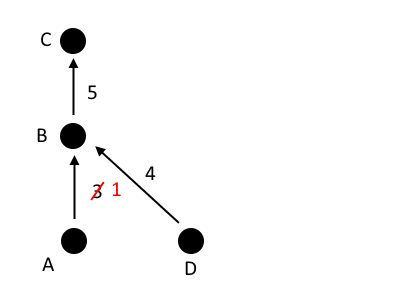

Here's where things get dicey and the principle of the Theory of Constraints comes into focus. Imagine now that item B requires the completion of both items A and D, which can be done simultaneously. You may notice now that the improvement we made in the turn time from A to B is inconsequential. 4 > 1, therefore giving us a total time of 4 + 5 = 9 units of time, up from 6.

More worrisome yet, imagine that we've got this huge unit of work spanning from E to C for a whopping 20. Just like before, the left chunk can be done in tandem with the right chunk, but ultimately, your final product isn't done until all of the segments connecting to C are done. The whole process just went from 9 to 20.

Finally, to belabor the point this theory intends to make, say we do the near-impossible and figure out a way to bring every other leg of production to a measly 1 unit. It should be clear by now that this is just work for work's sake and unambiguously a waste of time. Still 20.

Of course, real life is seldom as clear as this visual, but hopefully this better-informs your intuition. If you're ever unclear on what you should be pursuing, it's likely the answer to the question "what's the biggest thing preventing us from accomplishing our goals?" Note that this will (and should!) change and shift out of focus as you improve, but it's paramount that you always have a read on what your biggest constraint is.

The Three Ways

I mentioned above that The Three Ways are best thought of as graduating benchmarks for IT. This is true both in a process-health as well as complexity-to-accomplish sense and you cannot progress from one section until you've achieved mastery over it, as its successor is built right atop it.

First Way: Maximize Throughput

Recall that throughput is the relationship between what's coming in and what's going out. Another definition that is spun off of this interplay between Input and Output is Work in Progress (WIP). This is essentially the work that's assigned to be done and is either being actively worked on, or waiting in line behind other work to be worked on. At the end of the day, though, until your code is in production, no value is being generated for the business as a result of this project. Throughput is key.

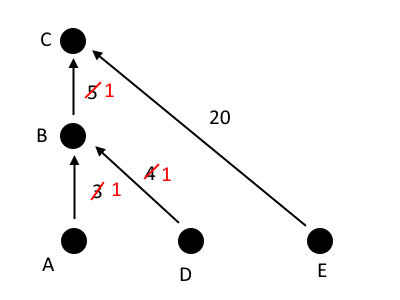

I always think about this concept in terms of pipes, and happy-accident, Google gave me an image that neatly touches back on our discussion of bottlenecks-- you're starting to see how these things are related, yeah?

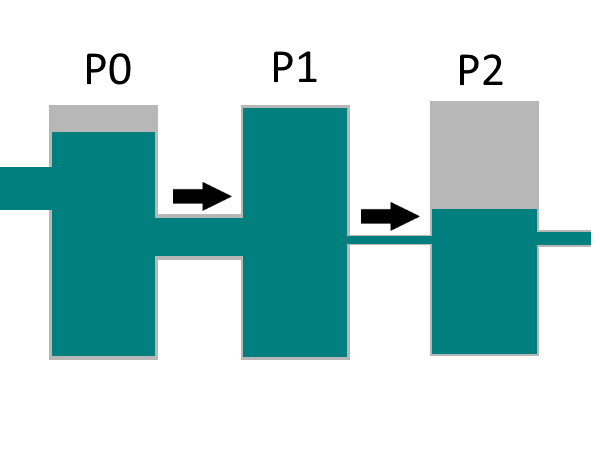

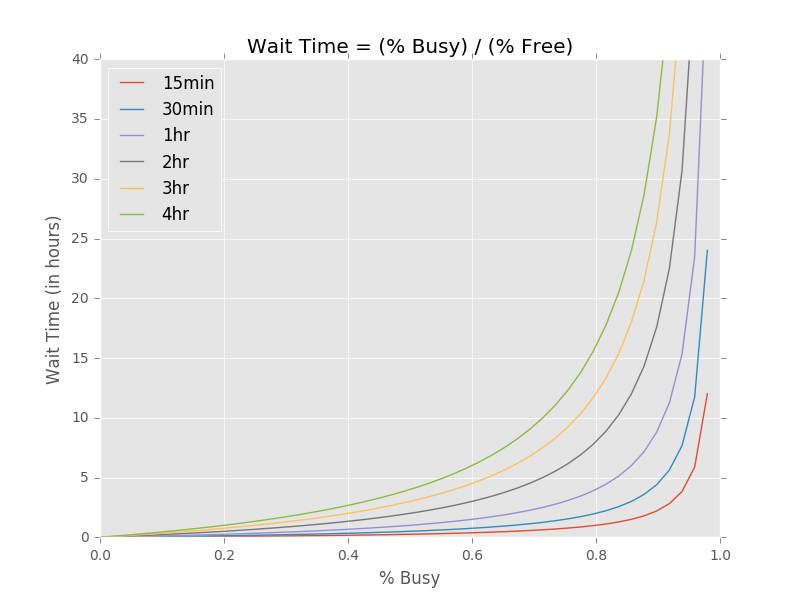

Though this image doesn't have a one-to-one representation with how we visualized work in The Theory of Constraints above, the mantra still holds: "Improvements anywhere besides the bottleneck are an illusion." Work comes into P0 from the left. But, as you can see, the flow of work is pretty dismal going from P1 to P2. What's more, is that based on this diagram, P1 is about to start hitting its capacity as well, as work/water is just sitting, stagnant, waiting to enter through P2. This is a great segue to what I found to be one of the most interesting conjectures that The Phoenix Project has, and that's about the toxicity of idle work. To highlight this notion, the book establishes some napkin-math-level intuition, examining roughly how long it'd take you to pick up new tasks based on how busy you are.

First, consider that all of your time sums up to 100%, split between time you're busy and time you're not.

Examining the two extremes, if you're completely busy (100%), you will never start working on a new thing without abandoning what you're already doing. We don't want that. On the other hand, you can, of course, immediately pick up something new if you've got nothing else going on (0%).

Naturally, this is a very simplified example, thick with assumptions. For straters, it assumes that each unit of work is uniform in time and complexity as well as not dependent on other items. It also doesn't consider the interplay between finishing asks and how that moves you along the curve. Finally, the visual is based on arbitrary units to demonstrate how rapidly this grows as you reach peak busy-ness.

But we can try and pin this closer (though still imperfectly) to reality by putting some units of time to these waiting periods and re-scaling the y-axis to illustrate total time in a 40 hr work week.

Now here's where this gets interesting. Non-zero buffer time to ramp up and work on a task is hardly a far-cry from practical application. As an analyst, if something new falls into my lap, I spend a good deal of time reading relevant email threads, asking questions, digging through unfamiliar data sources, setting up project repositories before I write a single line of code. Complicate this more with any variety of messy handoffs or scope creep, but hopefully the intuition is solid: if you were to generically track the total time it takes for "work" to get done (IT tasks, roller coaster lever-operation, line cooking), it's probable that the work items spend more time in a queue than actually being worked on.

Again, I'm representing a concept with a clearly imperfect example-- barely a scratch above pseudo-science with how many assumptions and weird units it employs-- with the hope that it informs your intuition. Thus, if we agree that WIP is the silent killer and want our work items to spend less time sitting around idle, then we want:

- To have some slack/flex time and not operate in the neighborhood of 100% busy-ness.

- Lower the ramp-up time it takes to get going on work.

- To minimize the number of handoffs, because that only scales this issue, multiplicatively.

- As an extension of this we also want to minimize the number of context switches in a day, as it follows the same pattern. Also it's better for my sanity.

Finally, if you have a good understanding of what work you typically have, you can establish processes that allow you to get better and better at doing familiar work through automation. Shout out to my kick-ass BA for seeing the writing on the wall and automating user story generation looooooooong before I ever picked up this book.

Second Way: Focus on Upstream Quality

No graphs or Paint.net for step two, but I feel pretty strongly about this one. The book highlights a few times throughout the several months of stumbling where the Development team is overwhelmingly self-congratulatory and heads out for drinks while the Operations team burns the candle at both ends just so the project can limp along to completion. More to the point, it highlights the need for the entire process chain to share in the wins/losses of these large-scale projects. It incentivizes the necessary dialogue that allows for correct restructuring and planning to occur to get ahead of needlessly-stressful photo finishes. After all, "It's not a good sign when they're still attaching parts of the space shuttle at liftoff." Step one is just encouraging a culture that values a level of downstream-empathy as opposed to just throwing it over the proverbial wall just because you can.

If you can foster enthusiasm to enact change (probably not a big "if", but YMMV), then you've done the hardest part of all of this, IMO. To accomplish a cleaner, more cohesive collaboration between your upstream and downstream teams, the following must occur:

- Constant flow of feedback from the right to the left. Like our last panel in the Theory of Constraints, the project isn't done until all work is done. By happenstance of where they fall in the flow of things, your upstream Dev team will really only have awareness of the issues immediately within their scope. It's important to seek out and then amplify downstream pain-points so that everyone has a clear understanding of where they should be focused. After all, anywhere else is probably an illusion, Michael.

- Creating Knowledge where we need it. Similar to above, if there's something that's routinely coming up as a complication to the work, generating good documentation around the kinds of issues that typically arise allow everyone to become more effective at addressing them.

- Of course, the ideal alternative to documentation is creating stop-gaps so that problems never make it very far down stream. This is where consideration of testing and good QA are key. Otherwise, it becomes unplanned or anti-work for the other areas, inflating their %Busy ratios and avalanching like these things often do.

All told, we should strive for systems that only flow forward. To introduce redundancy in the form of anti-work that makes its way up stream is to procrastinate taking on new work, as well as leaving the downstream folks to sit on their hands.

Third Way: Actually Doing That Agile Thing

Business agility isn't just about raw speed. It's about how good you are are at detecting and responding to changes in the market and being able to take larger and more calculated risks.

And this is that theoretical ideal, right? You've done a bang-up job automating the repetitive/mindless stuff. You have a good channel of feedback that affords the whole work stream a good guess at what the next hurdles are so they can plan accordingly. Getting to this stage all but guarantees that you're spending less time on unplanned and anti-work, allowing you to drill and develop scenario workflows to allow for better crisis resolution. As the book puts it "Murphy does exist, so you'll always have unplanned work, but it must be handled efficiently."

Suddenly, your time-management problem isn't a question of how to pull heroics out of your ass under duress, but how can we continue to go from good to great? Now we can start to introduce some unnecessary risk in the form of innovation. This is where the job becomes less about "How do I do the work in front of me?" but instead, "What haven't we tried that might have benefits nobody's considered before?" That's where the whole tech-disruption thing happens-- when you're not constantly at capacity doing rote work, siloed in an inefficient process, or putting out avoidable fires.

You figure out how to afford yourself more space and how to collaborate better. And this allows us more time to figure out to find even more time. It's like the opposite of the Tech Death Spiral.

Maybe this is an overly idealistic takeaway from this book. Hope not, but who knows.

In Practice

How This Translates to the Individual

In The Phoenix Project, the story kept returning to a character named Brent. Brent was great. He was pound-for-pound the most reliable and capable person working in IT. He was brought in on all-hands-on-deck situations and never ran into something that he couldn't eventually figure out. This got him a reputation, and perhaps rightfully so, as a go-to person when things get out of hand.

But Brent couldn't be everywhere. What's more is that the shortage of Brents wasn't a problem that could be solved by throwing money at it. They mention having tried that, but couldn't get the same bang for the buck with new hires that they had with Brent... if they even stuck around. Even on the ones that were pretty good replacements, the ramp-up time alone made it a difficult time and money investment to consider. When he'd go on vacation whole projects would all nearly grind to a halt because out of necessity, people kept relying on him to have a hand in everything. !!SPOILER!!, the book never once mentions any sort of contingency plan if Ben were to leave for a ton more money or have an accident that prevented him from returning. Frankly, I haven't got a clue how the story would have been written if that were the case. Point being, they had too much reliance on one person. Let's examine how management handled him as they progressed through the Three Ways.

- Removing WIP

- When Brent was spending the majority of his time firefighting and knocking out all of the one-off business asks that came his way it was, by definition, all time that he wasn't spending fixing upstream problems. Doing this would allow everyone to be better at the day-to-day work... at the expense of the day-to-day work. A real catch 22, if I haven't hammered this point home enough.

- Even during the calmer periods of time, Brent was never really plugging in as he was constantly being tapped by others to help debug bad deployment code, or was pulled in last-minute to explain how something he worked on at the expense of his current production work. Overlooking the instances where he gets uprooted and put in front of something because the "VP of So and So" was just shouting loud enough, the majority of Brent's poorly-spent time was driven by his desire to help the people around him. Hard to condemn that, right? But the sum of all of the "30 second" asks leads to a Death by 1000 Cuts situation.

- And so leadership goes to bat for Brett, setting him Out of Office and asking all unplanned work to get rerouted directly to the CIO if the requester has a problem. Pretty admirable, IMO.

- But in practice, this winds up shooting them in the foot even worse, as the number of projects that can't get finished without Brent start to come to light. Up until now, whenever Brent would step in and fix the problem, it would have taken him twice as long to create a work ticket than for him to just fix it, so he just did his thing. Soon, it's clear just how over-reliant the business has been on a lone resource, and how little knowledge-redundancy they've created.

- Creating and Embedding Knowledge

- Whenever we have to firefight or scramble, the level of documentation and flow of information is low. This is a direct product of the aforementioned attitude of "the only way to get work done is to do it" and leads to miserable levels of reproducability.

- To borrow one of my favorite quotes from the book: "Every time that we let Brent fix something that none of us can replicate, he gets smarter, and the entire system gets dumber."

- And so the system that they put into place-- which I love-- is the following:

- Brent doesn't get to touch a keyboard when he helps, but instead can only consult over the shoulder. They joke in the book that he's basically Hannibal Lecter, rolled out in a straight-jacket and wheelchair.

- Every time you ask for help, you have to document what you learned.

- Brent never works on the same problem twice. It will have been documented the first time, after all.

- It's that easy. Now Brent's assistance breaks the cycle of dependency and is instead timely collaboration and imparting the way he thinks and problem solves.

- As an added bonus, the more robust the documentation around the issues become, the more visibility there is into how much those issues happen. And there's a strongly proportional relationship between documentation and automatability.

- Donald Knuth coined a phrase that I love: "Science is knowledge which we understand so well that we can teach it to a computer"

- Non-functional Requirements

- Brent basically understands the whole system, top to bottom. And if he doesn't, he's got enough partial knowledge that it doesn't take him long to learn anything new. This attribute was always the reason that people turned to him in crises and in turn burned away whole months of his time, tapping him for help.

- Now, this same attribute gives him the unique perspective to see the system end-to-end and get to work, solving its bigger, more holistic problems. He works a level up of the project-work and instead does exciting things allowing automation of environment creation, standardizing version control, and streamlining production push requirements.

The transition of Brent's work from project to system tasks proved to be invaluable. The automation efforts evaporated the WIP (again, the silent killer). His focus on documentation and knowledge sharing reduced the dependencies on his time to finish out projects, but more generally made improvements at IT's bottleneck. Ultimately, once leadership got a good handle on where his time was best served in the long-run, the IT Death Spiral hit a real inflection point and things really started to turn around. Tech is weird.

How This Aggregates to a Team

Not everyone is Brent. Obviously. But not everyone has to be. There is no shortage of team building literature that gives far more insight than I've got for finding and fostering skills and thought across wildly-diverse individuals. Nurturing talent and passion in team members is no doubt the dogma of any good leader, but a plant doesn't flourish in unripe soil, and it's often unclear how to achieve that (otherwise why write a whole book on it, right?). In addition to keeping the Theory of Constraints and The Three Ways in mind, the following tangible steps will go a long way:

- Get visibility so you can understand the problem.

- Knowing is always better than not knowing.

- New work displaces the old. We constantly bump things up, but often don't know what got bumped down until people are upset at you.

- Whatever your intake process is, don't scrap it if it isn't optimal. To do so would sacrifice your situational awareness.

- Instead, if you're overwhelmed with more work than you can plan for effectively, continue to capture and then highlight work that bottlenecks your single-biggest constraint.

- As you improve that bottleneck, you can ease back into the broader picture by highlighting the top X business projects, projects that would improve IT quality of life, and items that are blocked.

-

Organize yourselves

- Forge ahead by developing a good intake process. The characters in the book were struggling to prioritize and get work done. That's a problem solved partially by the visibility gained above, but also by having better up-front requirement-gathering. This would also ideally be your avenue for solving Brent's untold number of taps and asks to do back-channel work.

- Chronicle the past by establishing a good system of version control. This allows for better disaster recovery and fosters a higher-sense of accountability due to the improved level of documentation implicit in most version control tools. A high-functioning system of version control corrects for botched handoffs where people are dropping things in shared drives and just saying "run/push this" with about as much direction and support as a newborn left on the steps of an orphanage.

-

Prioritize improvement of work over the work itself

"I don't want posters about quality and security. I want improvement of our daily work showing where it needs to be: In our daily work."

- We've all heard, and likely an untold number of times, that a team is greater than the sum of its parts. But to really see that come to life, you have to work hard at building the right culture. If you found any of this post compelling, I'd encourage you to think about how you might create a culture where:

- There's an undeniably high value in the time of others, and we share in the wins and losses beyond our own.

- There's a high level of trust and accountability, enabling people to have ownership over the problems they're solving, not just the tasks there's doing to get the work out.

- There's an emphasis on organizational learning and improvement. Teams reflect, having a consistent dialogue about what is and isn't working and -- just as, if not more, importantly-- routinely doing something about it.

- There's a shared goal of getting out from underneath the tech debt and process inefficiencies coupled with excitement about that would afford.

- There's a shared understanding that that only happens through valuing non-functional requirements and setting the next person in line up for success.

- We've all heard, and likely an untold number of times, that a team is greater than the sum of its parts. But to really see that come to life, you have to work hard at building the right culture. If you found any of this post compelling, I'd encourage you to think about how you might create a culture where:

That Was a Mouthful

So I suppose a constructive thing for me is to reflect on this deluge. It's one thing to spend dozens of hours reading a book, synthesizing, and then taking a few nights to flesh out a big ol' blog post. But "the great aim of education isn't knowledge, but action." So what's going to be different? Well:

- I will completely reevaluate my approach when asking for/giving assistance. What if instead of "doing the thing," the explicit, superseding goal is "figure out how to make doing this thing easier tomorrow"?

- I will think more about how we can introduce testing/monitoring into our workflow. If we can feel confident that our work is unassailable, then we can move onto bigger, farther-reaching projects (that solve for our biggest bottlenecks!) built atop a strong foundation.

- I, more concretely than "will change the way I'm thinking," am beginning work on putting the principles I learned from this book into action. Specifically, I'm turning a direct focus from a specific business area/problem and instead to the challenges the Analysts face.

- We spend at least as much time gathering data as we do analyzing it.

- We have a host of well-versioned queries we use to get at relevant chunks of data. What if instead of copy/pasting them into superqueries to do broader analysis, we could find a way to abstract that to a host of "base queries" and function calls?

- That way, we'd only have to write the query once, no matter how the underlying data definitions change over time.

- This would also implicitly grow the quality of our documentation as we build this out.

- All told, this presents an awesome opportunity to evangelize a lot of the things that I'm passionate about. I'll be collaborating through GitHub more, leading good dialogue about code quality and readability, and will have to figure out how the hell to successfully stitch together a Python library that will accomplish all of this.

- Not even close to having all of the details hammered out, nor mastery of the tools to do it. But this is the strongest I've felt about the impact I could make with the work I could do. Making myself 200% better or everyone around me, hell... even 3% better is a numbers game I'm alright playing.

My congratulations and apologies to anybody who stuck it out this far. Truth be told, this book caught me at a time where I was thinking a lot about this topic. Spent more time than I care to admit thinking about some of the consistent challenges I, and the others around me, face on the day-to-day and am happy that I parked myself in front of something that helped me find clarity on how to think more constructively about them. To summarize another quote from the book,

the job is to create an uninterrupted flow of fast and predictable work-- to minimize the impact of the inevitable unplanned and unforeseen, and in so doing, create a stable and trustworthy reputation for yourself and those around you.

Because after you can nail that, then you can turn your focus on leaving IT to understand business goals. You can foster strong relationships, backed by your capacity to comfortably do work that far exceeds the ship it/fix it life-cycle. You can create patterns of design so founded in quality and consistency that the job becomes less about the things you do and more about the problems you can solve.

And I think that's pretty damn exciting.