DMV Paradox, with a Side of Hash

Not necessarily related mood music. If this sounds like your thing and you're in SE Michigan, do yourself a favor and check them out.

Anyhow, I was out doing some errand running a few months ago and happened upon a dumb application of a famous math problem you may have heard of. I've wanted to get a post about this for some time now, but as I wrote, I realized that some of the math in this unrelated problem helped inform some intuition regarding a CS fundamental I've been tinkering with a whole lot lately.

The Birthday Paradox

Perhaps you've heard of the Birthday Paradox. Essentially, it states that if 23 people are in the same room, it's more likely than not that two of them have the same birthday. Moreover, if you have 75 people in the room, you can be 99.9% certain that at least one pair of them share a birthday.

This might not be immediately intuitive (hence the "paradox" part). I think mentally, everyone would easily accept 366 people in a room as a guarantee to see at least one pair, but to unpack why you can be half-certain with dramatically fewer people, you need to consider two things:

What's the probability of having a different birthday?

Let's assume a wild hypothetical where your birthday is on July 8th (and you procrastinate writing about an idea you had nearly 5 months). This means that there are 364 / 365 possible days that aren't your birthday-- 99.72% chance that a day selected at random is a different calendar day from your birthday.

And so you to turn to your neighbor and ask them their birthday. It's a different day, which could be expected as reasoned above.

Next you turn to your other neighbor and repeat the exercise. Note here that now you're entering a realm of compounding probabilities. In much the same manner that the probability that you flip two consecutive fair coins to heads is 1/4 (= 1/2 * 1/2), the probability that you find two consecutive different dates is (364/365 * 364/365) = 99.45%

You go on and repeat this until you've sampled 100 people and come up with (364 / 365) ^ 100 = 76% chance there's not a single match. But this is far from the 50% likelihood I quoted in the first paragraph-- and with seemingly 4 times as many people. What gives?

How many comparisons are you considering?

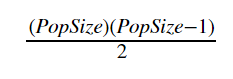

In our last example above, you were only considering 100 different pairs of people, and they were all you-centric. However, this fails to consider all of the checks that are happening in the room that don't involve you. Instead, we should think of the number of pairs in a room as the number of people times the number of potential partners, divided by two to correct for double-counting. This gives us:

In our example we reached out to 100 people, which means that there must've been 101 people in the room (100 plus you), giving us (101) * (100) / 2 = 5050 pairs. A few more comparisons than we were considering, yeah?

Merging the Two

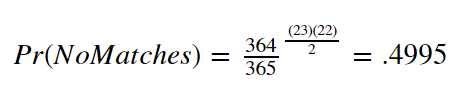

And so when you combine the probability of each check for different birthdays with the correct number of checks given a number of people in the room, you wind up with a neat equation for "Probability of No-Birthday-Matches" as follows:

Using this same equation, but tinkering with the number of people in the room (the exponent), we can see that the probability that there are no matches quickly goes to zero.

Indeed, we only need 23 people to be about 50% confident that there's no match. At 41 people, there's a 10% chance of that still being true, and at only 58, we're 99% confident that there's a birthday pair.

The DMV

So I'm sitting at the DMV waiting to getting my license renewed. It's a Wednesday afternoon, their "Super Hours" day where you don't have to take off work to do paperwork that you're legally required to do. Naturally it's a circus of unhappy people milling about.

However, they've got this cool feature nowadays where you can register with your phone number and they'll text you when you should head back (presumably while you aimlessly wander around the adjoining strip mall). The bureaucracy is still a headache, but the added convenience is certainly appreciated.

I didn't have anything better to do so I nabbed a seat and started bouncing back and forth between some trivia flash cards and the copy of Lost Boys by Orson Scott Card a friend had lent me (decent book, by the by, if a slow one). But then I look up and see:

``` ALL SERVICES

CUSTOMERS WAITING: 107

TOTAL FORECAST WAIT: 2 hr, 11 min ```

And underneath that there was a big board of positional rankings of everyone's phone numbers. Not the whole number, mind you, the last 4 digits. (Could you imagine? lol) It was organized into two columns of about 25 each and was, thankfully, moving at a pretty good pace.

After 10 minutes or so, I got excited because I thought that my number had finally entered the arena, despite being quoted an hour and a half wait. Alas, I was actually looking at someone else's phone number and had flipped an 8 and a 3 from afar. I was, of course, still not even on the board yet. Someone just had basically the same number as me. What are the odds?

Wait, What are the Odds?

And so we have a room full of people of variable length and a fixed number of possible values (phone numbers ending in 0000 to 9999 allows for 10,000 different values). This is basically the same problem as above, yeah?

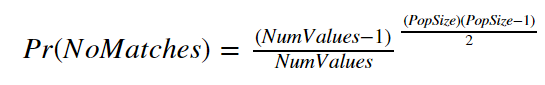

If we generalize the formula we used above a bit, we get

Where NumValues is the number of possible values that we could check for (365 calendar days in the Birthday Paradox) and PopSize is the number of people in the room.

A bit of computer nonsense™ later, and we can repeat the same "hold the possible values constant and tinker with the number of people" as above. We see that it takes about 118 people to be as certain as not that we're going to see duplicate numbers.

118 people. Considering that the board showed less than half of that a time, I think my error (in a hypothetical situation where I wasn't just reading wrong) seems to be a rare one, albeit not completely far-fetched.

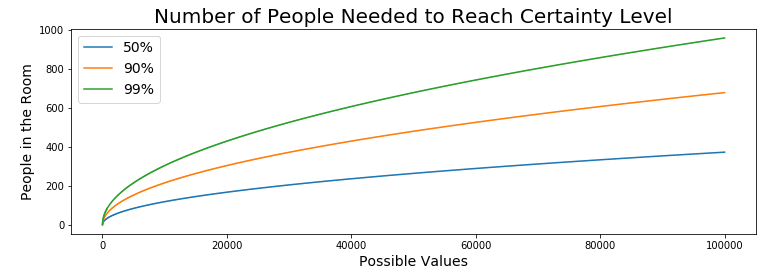

But did it stand out to you that if we stripped away the axes, these graphs looks pretty similar? Let's do some more digging.

Generalizing Even More

The only difference between the first and the second example is what base we held constant. In the Birthday Paradox, it was (364 / 365) and at the DMV, it was (9999 / 10000). From there, we arbitrarily increased the number of people in the room until we hit the break-even points were were monitoring in the visuals.

But what happens when we also arbitrarily increase the number of possible values at the same time?

There's a lot going on here, but one thing that I want to point out is that despite our "Number of potential values" axis being in the hundreds of thousands (bottom-right axis), our Population Size only needs to be in a few hundred to break that "more likely than not" barrier.

In fact, holding those target values (50%, 90%, 99%) equal, and playing with the different values in "People in the room" and "Possible Values" some interesting behavior emerges in the relationship between how many possibilities there are, and how few people you need to be more certain than not that there's a match somewhere.

- In the Birthday example, 23 people covered 365 values. 23 / 365 = 6.3%

- In the DMV example, 118 covered 10,000. 118 / 10,000 = 1.18%

- In the graphic above, 471 covered 160k. 0.294%

So where am I going with this?

Hash Values

If you aren't in the good handful of people who've been on the receiving end of my ranting on this topic, the elevator pitch about hash values goes: "You put some data into a hash function and it jumbles it. Like a lot. Conveniently, it also gives you a consistent output every time you put in an identical input." I won't go much deeper than that, but Chapter 5 of Grokking's Algorithms (a must-read, IMO) does a much better job than I could going into some of the finer details.

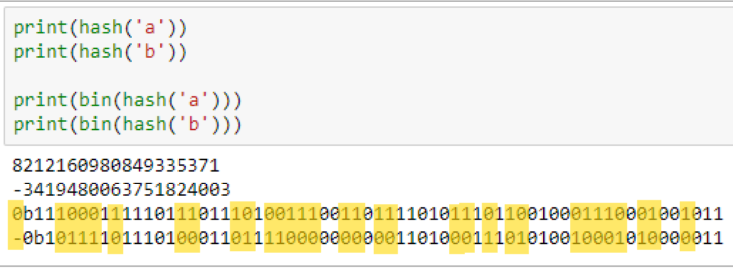

For instance, in Python, if you hash out the string values 'a' and 'b', they're represented as some crazy-long integers that are bafflingly different from one another, as a result of a multitude of differences in their bit representations (highlighted below).

SO...

Any time that I start in on teaching someone about Git/GitHub, I first give a lightning-fast overview of hash values. I think that a fundamental understanding of what they are allows a real solid appreciation for their role in powering the entire backend of Git.

If you want to know if two files are the same, don't go through and check every character, just compare their hash values. This extends to images. Unintelligible byte code. Whole projects. At the end of the day it's just 0s and 1s saved to disk and the hashing algorithm eats it up all the same. I leaned on the difference between 'a' and 'b' above, but the same would go for the difference in hash values between 'a' and 'A' or 'a' and 'a _'. Despite the inputs being very similar, the outputs are anything but. In order for this to work, though, you need to be certain that you're not accidentally going to wind up getting the same outputted hash values for different inputs; that hash values for the character 'a' vs all of the text in Crime and Punishment don't accidentally match.

By now, you probably see where I'm going with this. Let's look at how many "Possible Values" we're generating with these hash functions.

The binary strings I printed above are about 60 or so characters long, with each place holding a value of either 0 or 1. This winds up being 2^60 different possible values. About 1.15 quintillion. A whole lot.

The hashing scheme that Git uses is called the SHA-1 Hash, which, given some input data, spits out, count 'em, 40 hexadecimal characters with 16 possible values (0-9A-F, instead of just 0-9). I always emphasize the ludicrous amount of possible values for this string to take and how useful this is in ensuring that you've got a unique version of your file.

But as I pointed out above, as this whole "look for pairs in the room" model scales to infinity, the ratio of "People needed" in order to achieve "more likely than not there's a match" divided by "Possible values" tends to, basically, zero.

There are 16^40 possible SHA-1 Hash Values. This is expressed as 1.462e48 (or times 10 to the 48th power), measured in the quindecillions-- a word Google auto-correct insists doesn't exist as I type this.

If we go back to our "people in a room" idea, trying to to cover the 50% likelihood number for this unfathomably large possibility-space, we need 1.42e24 different folks. Or 1.42 septillion. If our aim is ensure uniqueness with our hashing algorithm, having septillions of possible file states worth of wiggle room ain't bad.

At Scale

However, as we continue to tack 'e' and some combination of numbers to the end of a decimal, I worry that the sheer magnitude of the numbers we're talking about gets lost along the way. Let's march back through our earlier examples:

- Birthday: 23 people covered 365 values. 23 / 365 = 6.3%

- DMV: 118 covered 10,000. 118 / 10,000 = 1.18%

- 471 covered 160k. 0.294%

Here, 1.42e24 covers 1.46e48. 1.42e24 / 1.46e48 = 9.739e-25.

9.734e-25. Let me help you with that.

For comparison, the ratio you get when you divide the diameter of a Hydrogen atom by the average distance between Pluto and the Sun comes in at 8.966e-24, which is STILL not small enough to pass this covering ratio.

Wow.

Hopefully this brief detour into from trivia to CS

Conclusion

Hopefully now the notion of it only taking 23 people in a room to find a pair of matching birthdays holds a bit more water, intellectually. Because as this problem scales, the power of compounding pairs of people is just wild.

As for the rest of the day at the DMV, I spent the couple days leading up to that Wednesday ruminating on what 7 letter word I could create with a Block M and 6 other letters.

And then an ah-ha moment! I could pay homage to one of my favorite movies, thus publicly memorializing my inaccessible pop culture humor.

And so after a bit of l337 5p34k finagling, I drove off with

It was only later that I realized that "there is an 'I' in 'meatpie'" is perfectly at odds with the fact that there is no "I" on my plate.

Notes

For the sake of demonstration, I simplified our model a bit with some rounder math and some relaxed assumptions.

- No Leap Day

- Assuming a uniform distribution of birthdays

- Not leaning on any conditional probability in my calculation

If you found yourself interested in this idea of a hash value interesting at all, that's basically what's powering the backend of BitCoin. And if you want to be on the forefront of the new buzzword in tech, apparently you want to spend some time googling "Block Chain" in the near future (shout out to my good friend Patrick for keeping me current).

Cheers,

-Nick